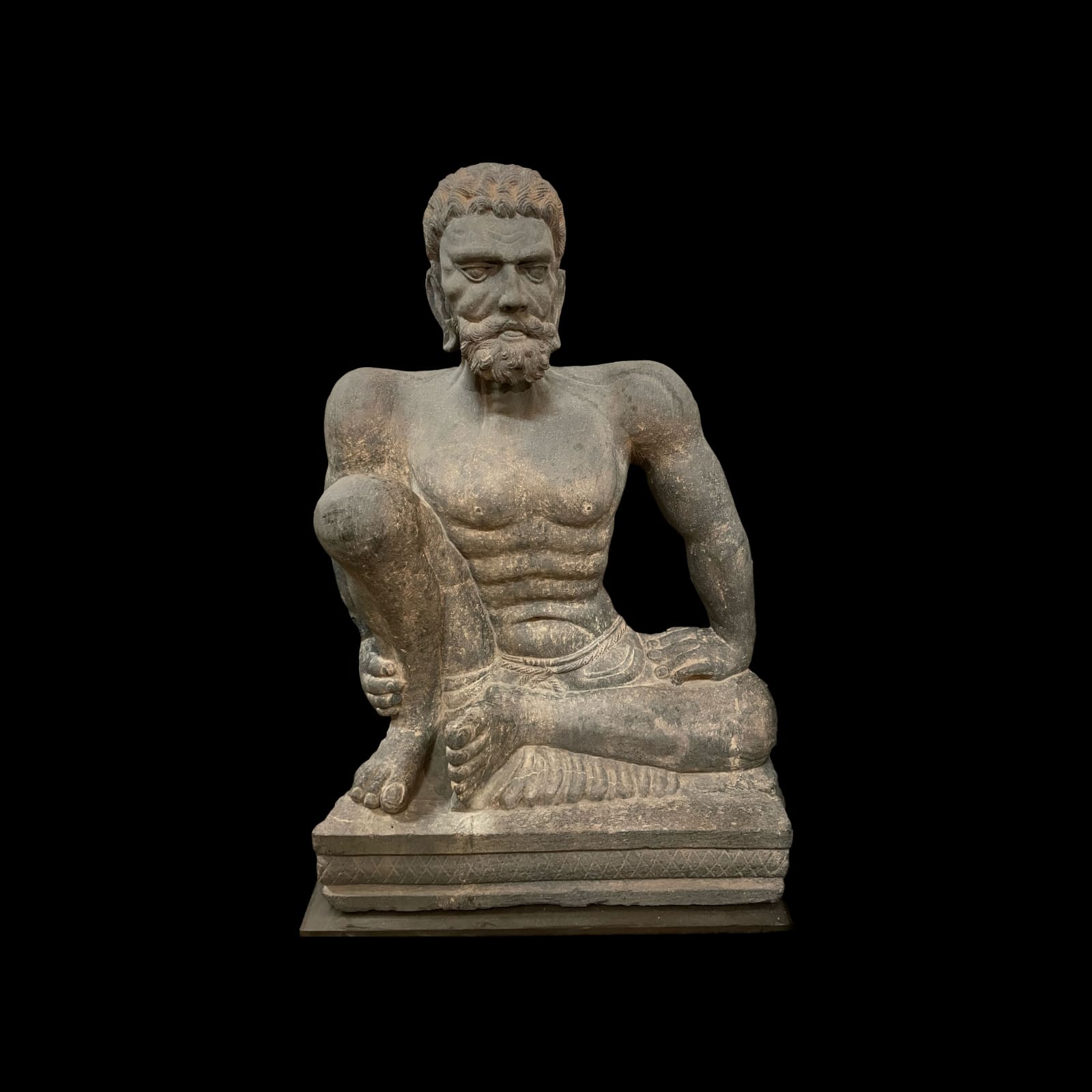

Gandhara Schist Sculpture of an Ascetic, 2nd Century CE - 3rd Century CE

Schist

167.6 x 101.6 x 55.9 cm

66 x 40 x 22 in

66 x 40 x 22 in

PF.5533

Further images

The ancient civilization of Gandhara thrived in the region of northeastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. Situated at a confluence of trading paths along the Silk Route, the area was flooded...

The ancient civilization of Gandhara thrived in the region of northeastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. Situated at a confluence of trading paths along the Silk Route, the area was flooded in cultural influences ranging from Greece to China. Gandhara flourished under the Kushan Dynasty and their great king, Kanishka, who traditionally given credit for further spreading the philosophies of Buddhism throughout central Asia and into China. This period is regarded as the most important era in the history of Buddhism. After the conquests of Alexander the Great, the creation of Graeco-Bactrian kingdoms, and the general Hellenization of the subcontinent, Western aesthetical tastes became prominent. Greek influence began to permeate into Gandhara. Soon sculptors based the images of the Buddha on Graeco-Roman models, depicting Him as a stocky and youthful Apollo, complete with long-lobed ears and loose monastic robes similar to a Roman toga. The extraordinary artistic creations of Gandhara reveal link between the worlds of the East and West.

An extremely important Gandharan statue, this piece depicts the figure of an ascetic complete with a highly expressive physiognomy. Overall, the sculpture employs a statuary type seen in the so-called “Atlas” figures of Gandharan art, semi-divine beings generally with wings which are shown squatting on some lower registers of votive stupas. They have been named “Atlas” figures because they appear to support the superstructure above them. This sculpture is posed in the characteristic Atlas stance with his right leg bent but held vertically while the left one is placed flat on the ground; the arrangement of the hands – the right grasping the right ankle and the left placed near the knee – is also consistent with the Atlas iconography. However, the rendition of the head and the monumental scale of the figure are both unique. Although the arms are quite muscular, the torso is rather thin with the rib structure protruding. The head is that of an older, bearded man. The skin on the neck is taught, seemingly pulled upward, revealing the bony structure of the spinal column, a detail that frequently occurs in representations of ascetics of the fasting Buddha. The identification of this figure as an ascetic is also based on the small loincloth secured by a rope, a characteristic costume seen on images of such holy men. The large scale of the figure, together with its portrait-like physiognomy, suggests that this may be a statue of a particular ascetic, perhaps one of several which appear in Buddhist stories, or might even be intended to be a representation of a particular individual. This figure is, to our knowledge, the largest example of a figure from the “Atlas” family and presents an impressive fusion of the classical tradition of the west within the Gandharan artistic milieu.

An extremely important Gandharan statue, this piece depicts the figure of an ascetic complete with a highly expressive physiognomy. Overall, the sculpture employs a statuary type seen in the so-called “Atlas” figures of Gandharan art, semi-divine beings generally with wings which are shown squatting on some lower registers of votive stupas. They have been named “Atlas” figures because they appear to support the superstructure above them. This sculpture is posed in the characteristic Atlas stance with his right leg bent but held vertically while the left one is placed flat on the ground; the arrangement of the hands – the right grasping the right ankle and the left placed near the knee – is also consistent with the Atlas iconography. However, the rendition of the head and the monumental scale of the figure are both unique. Although the arms are quite muscular, the torso is rather thin with the rib structure protruding. The head is that of an older, bearded man. The skin on the neck is taught, seemingly pulled upward, revealing the bony structure of the spinal column, a detail that frequently occurs in representations of ascetics of the fasting Buddha. The identification of this figure as an ascetic is also based on the small loincloth secured by a rope, a characteristic costume seen on images of such holy men. The large scale of the figure, together with its portrait-like physiognomy, suggests that this may be a statue of a particular ascetic, perhaps one of several which appear in Buddhist stories, or might even be intended to be a representation of a particular individual. This figure is, to our knowledge, the largest example of a figure from the “Atlas” family and presents an impressive fusion of the classical tradition of the west within the Gandharan artistic milieu.

Literature

V28