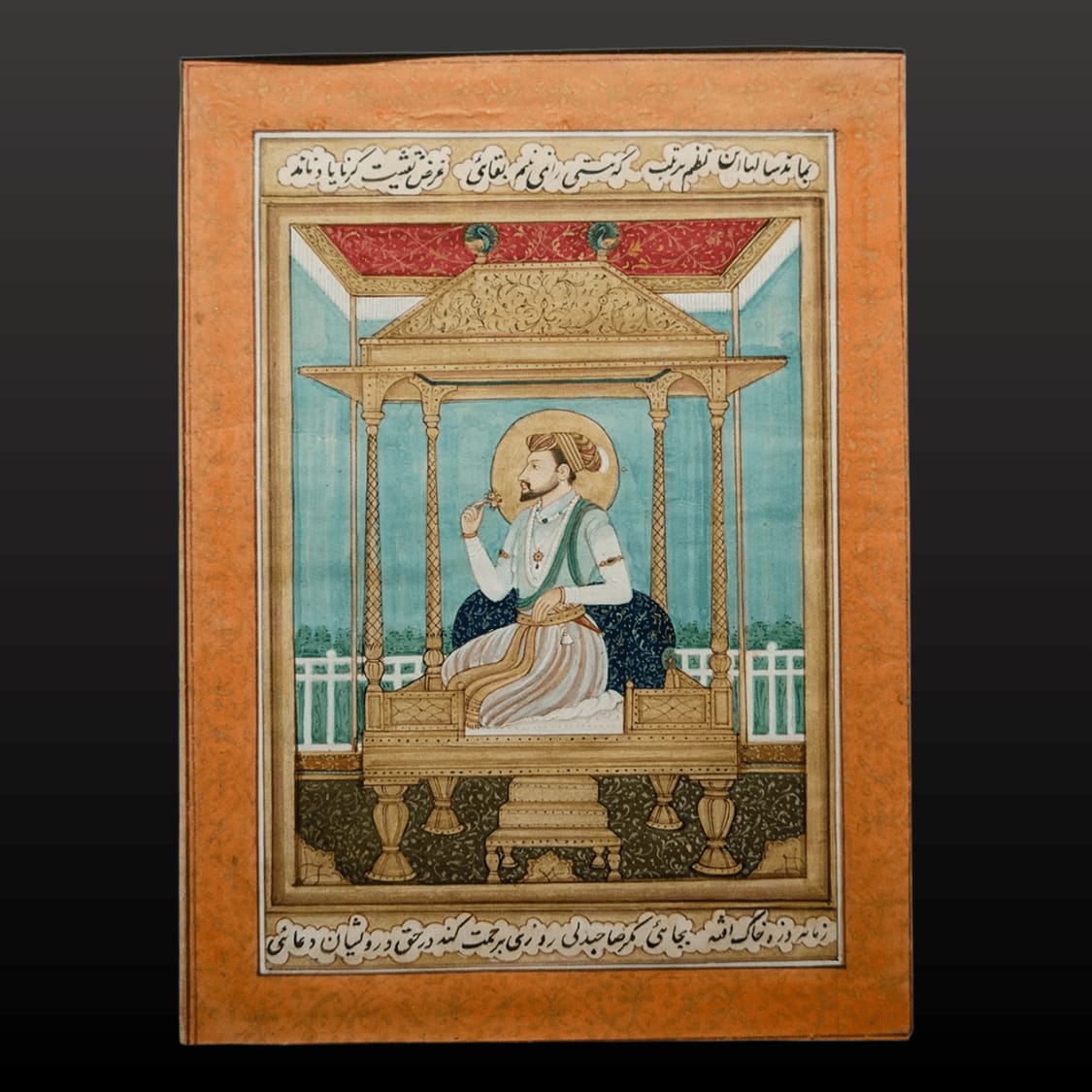

Mughal-Style Miniature of Shah Jahan, Enthroned, Nineteenth Century AD

Opaque Watercolour, Ink, Paper

Dimensions not given

CC.276

Further images

When Mumtaz Mahal died during childbirth in AD 1631, her husband, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, was wracked with grief. He was given to convulsive fits of tears, gave up...

When Mumtaz Mahal died during childbirth in AD 1631, her husband, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, was wracked with grief. He was given to convulsive fits of tears, gave up listening to music, and ceased dressing in extravagant clothes. Travelling to console his grief, he grew enamoured with a plot of land south of Agra. The local ruler, Raja Jai Singh, donated the land to create a mausoleum for Mahal. The resulting building, the extraordinary white marble Taj Mahal, is rightly now one of the most famous buildings in the world. The shining onion domes and domelets have become a symbol of the Indian nation, and equally representative of the phenomenal artistic achievements of this vast subcontinent. This is just one example of Shah Jahan’s extraordinary propensity for building, and for his remarkable sponsorship of the arts.

Born into the Mughal royal family, his grandfather, the great Emperor Akbar, favoured the young prince, third son of his father Jahangir and not ever likely to attain the throne. Akbar called him Khurram (‘joyous’ in Persian), and had him raised in his own court rather than Jahangir’s. Later, the prince became a great general, dealing with the Deccans on the Mughal’s southern border, and restoring Mughal control in the region. Upon his return in AD 1617, his father Jahangir – by now Emperor – gave him the title Shah Jahan (‘King of the World’), presented him with his own throne, raised him to the ultimate military rank, and declared him ‘my first son in everything’. Jahan then competed for predominance among his brothers, defeating them militarily and establishing his dominance. Upon his father’s death, he acceded to the throne, executing his rivals – even family members. As Emperor, however, he was renowned for his charity and compassion. When in AD 1630 a famine in Deccan led to the deaths of two million, Jahan set up free kitchens (langar) to distribute food to the masses. He oversaw a period of economic and cultural fluorescence; by the estimate of economist Angus Maddison, the Mughal Empire accounted for around 24% of global economic output by AD 1700, overtaking China as the wealthiest country on Earth. But Jahan could be brutal, especially in the promotion of Islam at the expense of Hinduism. By one estimate, he destroyed more than seventy temples in the city of Veranasi alone. As a result, rebellions against Shah Jahan were not uncommon, added to which, he also had confrontation with European powers, most notably the Portuguese, who he evicted from their trading post in Bengal, and whose Jesuit churches he persecuted.

The glorious reign of Shah Jahan, then, was considered one of the most important in Indian history. When, in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, India was controlled first by the East India Company, and later by the British government, the image of Shah Jahan became an important reminder of India’s glorious and independent past, and of a ruler whose resistance to the Europeans was legendary. Miniature painting, the characteristic Mughal art form, had been introduced in the reign of Jahan’s grandfather Akbar, imported from Persia and, ultimately, from Ming China. Mughal court painting was a rigid and formal discipline, largely aimed at reproducing secular images from the Mughal past. Compared to the looser and freer paintings produced in the regional Indian courts, the imperial discipline was programmatic and formulaic, but no less beautiful for it. But, despite being a fiercely associated with independent Mughal India, the relationship between miniature painters and the Europeans who came to dominate the subcontinent were ambivalent and complex. Numerous paintings were produced for the European export market, creating an appreciation for the Indian aesthetic. It is probably in this tradition that this remarkable portrait of Shah Jahan sits.

Formulated as a book page, it is in fact more likely that this painting was produced for an album (muraqqa). In the centre, Shah Jahan is resplendent on the Peacock Throne, the bejewelled and golden throne of the Mughal Emperors which was locked away in the Red Fort in Delhi. The throne itself sits on four baluster legs, upon which is a platform with a low railing around it. From this platform rise four colonnettes which hold up a canopy with a pitched roof. The throne is set in a richly decorated room, with an elegant black carpet, turquoise-blue walls with black and gold wainscotting, and a ceiling covered in a rich red foliate roof-hanging. The perspective is apparent on the ceiling and upper walls, but not on the lower half of the painting. Shah Jahan himself sits on the throne in a relaxed pose, large pillows strewn around him for his comfort. Resting on his knees, the Shah wears billowing paijama style trousers (from which derives the English word pyjama), a patka sash around his waist, and a tight-fitting shirt of a sheer material which reveals much of the Emperor’s physique. He wears an extended pearl necklace, and a second diamond necklace with a heavy pendant. On his head is a pagri turban, embellished with a kalgi bejewelled turban ornament. Shah Jahan’s immediately recognisable features – straight nose, languid eyes, trimmed beard, pale skin – are rendered with commendable attention to detail. He holds in his hand a small flower, probably a Damask rose (Rosa damascena), a cultivated flower which does not exist in the wild, and became symbolic of the Mughal monarchy. Around the Shah’s head is a halo, a common attribute of Mughal rulers.

Above and below the image are Persian text, set in the saffron-coloured border replete with vegetal arabesques in gold leaf, which reveal something of the intentions of the artist. Above the Emperor, the phrase ‘let the disciplined order that exists in my heart remain for many years’. Below, the signature of the painter, Zanameh Vazeh Khak, a Persian name, and the phrase: ‘by Allah, may the displaced people have mercy on the governors.’ It is eminently possible that the image of this great resistor of European rule may have been intended as a protest against British colonialism in the subcontinent. This remarkable image of Shah Jahan is modelled on one of the most famous paintings of the Shah, attributed to the Indian painter Govardhan and produced around AD 1635. Now in the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (MS.45.2007), the image became one of the most imitated in Indian art.

References: other Nineteenth Century AD copies of the Govardhan portrait of Shah Jahan can be found in London (Victoria and Albert Museum IM.113-1921) and New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 13.228.53).

Translation: upper register: ‘let the disciplined order that exists in my heart remain for many years’; lower register: ‘Zanameh Vazeh Khak; by Allah, may the displaced people have mercy on the governors.’

Born into the Mughal royal family, his grandfather, the great Emperor Akbar, favoured the young prince, third son of his father Jahangir and not ever likely to attain the throne. Akbar called him Khurram (‘joyous’ in Persian), and had him raised in his own court rather than Jahangir’s. Later, the prince became a great general, dealing with the Deccans on the Mughal’s southern border, and restoring Mughal control in the region. Upon his return in AD 1617, his father Jahangir – by now Emperor – gave him the title Shah Jahan (‘King of the World’), presented him with his own throne, raised him to the ultimate military rank, and declared him ‘my first son in everything’. Jahan then competed for predominance among his brothers, defeating them militarily and establishing his dominance. Upon his father’s death, he acceded to the throne, executing his rivals – even family members. As Emperor, however, he was renowned for his charity and compassion. When in AD 1630 a famine in Deccan led to the deaths of two million, Jahan set up free kitchens (langar) to distribute food to the masses. He oversaw a period of economic and cultural fluorescence; by the estimate of economist Angus Maddison, the Mughal Empire accounted for around 24% of global economic output by AD 1700, overtaking China as the wealthiest country on Earth. But Jahan could be brutal, especially in the promotion of Islam at the expense of Hinduism. By one estimate, he destroyed more than seventy temples in the city of Veranasi alone. As a result, rebellions against Shah Jahan were not uncommon, added to which, he also had confrontation with European powers, most notably the Portuguese, who he evicted from their trading post in Bengal, and whose Jesuit churches he persecuted.

The glorious reign of Shah Jahan, then, was considered one of the most important in Indian history. When, in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, India was controlled first by the East India Company, and later by the British government, the image of Shah Jahan became an important reminder of India’s glorious and independent past, and of a ruler whose resistance to the Europeans was legendary. Miniature painting, the characteristic Mughal art form, had been introduced in the reign of Jahan’s grandfather Akbar, imported from Persia and, ultimately, from Ming China. Mughal court painting was a rigid and formal discipline, largely aimed at reproducing secular images from the Mughal past. Compared to the looser and freer paintings produced in the regional Indian courts, the imperial discipline was programmatic and formulaic, but no less beautiful for it. But, despite being a fiercely associated with independent Mughal India, the relationship between miniature painters and the Europeans who came to dominate the subcontinent were ambivalent and complex. Numerous paintings were produced for the European export market, creating an appreciation for the Indian aesthetic. It is probably in this tradition that this remarkable portrait of Shah Jahan sits.

Formulated as a book page, it is in fact more likely that this painting was produced for an album (muraqqa). In the centre, Shah Jahan is resplendent on the Peacock Throne, the bejewelled and golden throne of the Mughal Emperors which was locked away in the Red Fort in Delhi. The throne itself sits on four baluster legs, upon which is a platform with a low railing around it. From this platform rise four colonnettes which hold up a canopy with a pitched roof. The throne is set in a richly decorated room, with an elegant black carpet, turquoise-blue walls with black and gold wainscotting, and a ceiling covered in a rich red foliate roof-hanging. The perspective is apparent on the ceiling and upper walls, but not on the lower half of the painting. Shah Jahan himself sits on the throne in a relaxed pose, large pillows strewn around him for his comfort. Resting on his knees, the Shah wears billowing paijama style trousers (from which derives the English word pyjama), a patka sash around his waist, and a tight-fitting shirt of a sheer material which reveals much of the Emperor’s physique. He wears an extended pearl necklace, and a second diamond necklace with a heavy pendant. On his head is a pagri turban, embellished with a kalgi bejewelled turban ornament. Shah Jahan’s immediately recognisable features – straight nose, languid eyes, trimmed beard, pale skin – are rendered with commendable attention to detail. He holds in his hand a small flower, probably a Damask rose (Rosa damascena), a cultivated flower which does not exist in the wild, and became symbolic of the Mughal monarchy. Around the Shah’s head is a halo, a common attribute of Mughal rulers.

Above and below the image are Persian text, set in the saffron-coloured border replete with vegetal arabesques in gold leaf, which reveal something of the intentions of the artist. Above the Emperor, the phrase ‘let the disciplined order that exists in my heart remain for many years’. Below, the signature of the painter, Zanameh Vazeh Khak, a Persian name, and the phrase: ‘by Allah, may the displaced people have mercy on the governors.’ It is eminently possible that the image of this great resistor of European rule may have been intended as a protest against British colonialism in the subcontinent. This remarkable image of Shah Jahan is modelled on one of the most famous paintings of the Shah, attributed to the Indian painter Govardhan and produced around AD 1635. Now in the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (MS.45.2007), the image became one of the most imitated in Indian art.

References: other Nineteenth Century AD copies of the Govardhan portrait of Shah Jahan can be found in London (Victoria and Albert Museum IM.113-1921) and New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 13.228.53).

Translation: upper register: ‘let the disciplined order that exists in my heart remain for many years’; lower register: ‘Zanameh Vazeh Khak; by Allah, may the displaced people have mercy on the governors.’