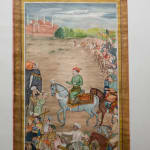

Mughal Miniature, depicting Jahangir receiving a Prisoner, Eighteenth to Nineteenth Century AD

Opaque Watercolour and Gold, on Paper

22.9 x 13.7 cm

9 x 5 3/8 in

9 x 5 3/8 in

CC.352

The glorious Mughal Empire was founded by Babur, a descendant of the great warrior-king Tamerlane (also known as Timur), in AD 1526. Their rule saw a remarkable explosion of the...

The glorious Mughal Empire was founded by Babur, a descendant of the great warrior-king Tamerlane (also known as Timur), in AD 1526. Their rule saw a remarkable explosion of the arts in India, and a mixing of Muslim philosophy and religion with the native Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh religions. Under their rule, India was perhaps the wealthiest nation on Earth, rivalling Ming and later Qing Dynasty China, fuelled by the trade in tea, spices, gold and precious stones. The fourth of the Mughal Emperors was Jahangir, who was torn between the machinations of his own family, and inexorable rise of the English (later British) East India Company, who would, over the next century, begin to take direct control of large swathes of northern India. His reign, though less glorious than those of his predecessors Babur and Akbar, or his successor Shah Jahan, was nonetheless well-remembered by later generations, thanks to the record of his life in the semi-mythical autobiography Jahangirnama, and scenes from his life were popular subjects for miniatures.

This scene is taken from a famous miniature now held in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin (34.5); painted in the Seventeenth Century AD by one of the Mughal court artists, this miniature depicted Jahangir’s second visit to the tomb of his predecessor, Akbar, in AD 1619. His first visit, made in AD 1608, was explicitly conducted on foot in homage to his father. Jahangir had been responsible for Akbar’s mausoleum, which is depicted at the back of this scene. Constructed from red sandstone, with dazzling white marble details, the tomb was, and remains, an impressive structure. Akbar’s mausoleum was built in the countryside near the city of Agra, and was an important architectural and conceptual precursor to the Taj Mahal, India’s most famous tomb, which was built by Jahangir’s successor Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz Mahal. This vividly drawn scene is well-observed, depicting Jahangir on horseback amid a throng of his attendants. Jahangir is depicted in green, a favourite colour of the Mughal Monarchs, perhaps given the association with jade which they favoured. His traditional turban, commonly worn by Mughal Emperors, which contains an emerald pin with a long plume, which was considered the equivalent to ‘crown jewels’. The Mughals loved emeralds, which they called ‘the Tears of the Moon’, and which were often richly carved with figural motifs or inscriptions, rather than being merely faceted like a modern jeweller might.

Jahangir has peeled off from the side of his column of attendants, who continue to parade around him in a stately procession. He sits opposite an elephant – a symbol of his power and prestige – whose mahout (rider) leans down against the animal’s head to observe the ensuing scene. A prisoner has been brought before Jahangir, bent down forwards in the face of the Emperor, and firmly held in place by. A turbaned official in black. He is almost certainly a criminal rather than a prisoner of war, and is being presented to Jahangir to pass some kind of final judgement. Alas, this probably did not go well for the criminal in question: according to the French traveller François Bernier, Jahangir had huge numbers of criminals executed in imaginative and sadistic ways to satisfy his own amusement. Perhaps this brutal reputation enhanced the appeal of this scene to the Eighteenth- or Nineteenth-Century AD copyist who rendered it in such lively form, as well as to the potential buyers of such a miniature, who were most probably Europeans residing in India. While the artist did not originate this composition, the skill with which it is executed is extremely high. The detail is exceptional, and the luminosity of the colours is breath-taking. The style is so lose to that of the Mughal court artists that one wonders whether this piece was painted by a current or former court artist making money in his off time. This would certainly explain the access the artist had to the original composition, which was certainly held in the Mughal imperial libraries; the closeness of the depiction (one slight difference is the omission of a tent or marquee in dusky blue behind the treeline at the upper right of the picture) to the original certainly indicates that the artist had seen and studied it.

References: this is an Eighteenth or Nineteenth Century AD copy of a Seventeenth Century AD original, painted near-contemporaneously with Jahangir’s visit to Akbar’s tomb in AD 1619, which can now be found in Dublin (Chester Beatty Library 34.5).

This scene is taken from a famous miniature now held in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin (34.5); painted in the Seventeenth Century AD by one of the Mughal court artists, this miniature depicted Jahangir’s second visit to the tomb of his predecessor, Akbar, in AD 1619. His first visit, made in AD 1608, was explicitly conducted on foot in homage to his father. Jahangir had been responsible for Akbar’s mausoleum, which is depicted at the back of this scene. Constructed from red sandstone, with dazzling white marble details, the tomb was, and remains, an impressive structure. Akbar’s mausoleum was built in the countryside near the city of Agra, and was an important architectural and conceptual precursor to the Taj Mahal, India’s most famous tomb, which was built by Jahangir’s successor Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz Mahal. This vividly drawn scene is well-observed, depicting Jahangir on horseback amid a throng of his attendants. Jahangir is depicted in green, a favourite colour of the Mughal Monarchs, perhaps given the association with jade which they favoured. His traditional turban, commonly worn by Mughal Emperors, which contains an emerald pin with a long plume, which was considered the equivalent to ‘crown jewels’. The Mughals loved emeralds, which they called ‘the Tears of the Moon’, and which were often richly carved with figural motifs or inscriptions, rather than being merely faceted like a modern jeweller might.

Jahangir has peeled off from the side of his column of attendants, who continue to parade around him in a stately procession. He sits opposite an elephant – a symbol of his power and prestige – whose mahout (rider) leans down against the animal’s head to observe the ensuing scene. A prisoner has been brought before Jahangir, bent down forwards in the face of the Emperor, and firmly held in place by. A turbaned official in black. He is almost certainly a criminal rather than a prisoner of war, and is being presented to Jahangir to pass some kind of final judgement. Alas, this probably did not go well for the criminal in question: according to the French traveller François Bernier, Jahangir had huge numbers of criminals executed in imaginative and sadistic ways to satisfy his own amusement. Perhaps this brutal reputation enhanced the appeal of this scene to the Eighteenth- or Nineteenth-Century AD copyist who rendered it in such lively form, as well as to the potential buyers of such a miniature, who were most probably Europeans residing in India. While the artist did not originate this composition, the skill with which it is executed is extremely high. The detail is exceptional, and the luminosity of the colours is breath-taking. The style is so lose to that of the Mughal court artists that one wonders whether this piece was painted by a current or former court artist making money in his off time. This would certainly explain the access the artist had to the original composition, which was certainly held in the Mughal imperial libraries; the closeness of the depiction (one slight difference is the omission of a tent or marquee in dusky blue behind the treeline at the upper right of the picture) to the original certainly indicates that the artist had seen and studied it.

References: this is an Eighteenth or Nineteenth Century AD copy of a Seventeenth Century AD original, painted near-contemporaneously with Jahangir’s visit to Akbar’s tomb in AD 1619, which can now be found in Dublin (Chester Beatty Library 34.5).