Sumerian Cuneiform Tablet, 2029 BCE

1.85 x 2.44

AM.0072

Further images

Sumerian cuneiform is one of the earliest known forms of written expression. First appearing in the 4th millennium BC in what is now Iraq, it was dubbed cuneiform (‘wedge-shaped’) because...

Sumerian cuneiform is one of the earliest known forms of written expression. First appearing in the 4th millennium BC in what is now Iraq, it was dubbed cuneiform (‘wedge-shaped’) because of the distinctive wedge form of the letters, created by pressing a reed stylus into wet clay. Early Sumerian writings were essentially pictograms, which became simplified in the early and mid 3rd millennium BC to a series of strokes, along with a commensurate reduction in the number of discrete signs used (from c.1500 to 600). The script system had a very long life and was used by the Sumerians as well as numerous later groups – notably the Assyrians, Elamites, Akkadians and Hittites – for around three thousand years. Certain signs and phonetic standards live on in modern languages of the Middle and Far East, but the writing system is essentially extinct. It was therefore cause for great excitement when the ‘code’ of ancient cuneiform was cracked by a group of English, French and German Assyriologists and philologists in the mid 19th century AD. This opened up a vital source of information about these ancient groups that could not have been obtained in any other way.

Cuneiform was used on monuments dedicated to heroic – and usually royal – individuals, but perhaps its most important function was that of record keeping. The palace-based society at Ur and other large urban centres was accompanied by a remarkably complex and multifaceted bureaucracy, which was run by professional administrators and a priestly class, all of whom were answerable to central court control. Most of what we know about the way the culture was run and administered comes from cuneiform tablets, which record the everyday running of the temple and palace complexes in minute detail, as in the present case. The Barakat Gallery has secured the services of Professor Lambert (University of Birmingham), a renowned expert in the decipherment and translation of cuneiform, to examine and process the information on these tablets. His scanned analysis is presented here. This is an extremely rare text recording the making of a statue of the third king of the Ur dynasty, Amar-Suena. Kings were accorded divine status in Sumerian society and this may be the reason for the present document.

Professor Lambert’s translation is provided below:

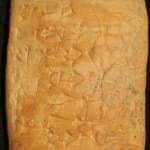

Clay tablet, 62x47mm., with a total of 17 lines of Sumerian cuneiform on obverse and reverse. An administrative document from the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur, dated to the 9th year of Shu-Sin, fourth king of the dynasty, c. 2029 B.C. It is a rare and important tablet, and it is thus all the more to be regretted that not everything can be read. The scribe rolled the surface of the tablet with his cylinder seal after he ad written it, and in doing so obscured many of the signs. In addition there is some surface corrosion and one rejoined patch. The obverse is most affected, the reverse much less so. The tablet is a record of the making of a statue of the third king of the dynasty, Amar-Suena, father of the then reigning king. It is well known that these kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur were accorded divine status even in their lifetimes, and this may be the reason for the present document:

Translatio

2 . . . .

5 carpenter

1 leather worker: for 1 day to make a statue of the . . . king in the . . . templ

When they took the statue of Amar-Suena fom the inspection podium to the . . . temple, it was thanks to Puta-padda, thanks to Lu-Ninshuburaka and thanks to Nanna-dalla, metal workers of the kin

Month: barley harves

Year: Shu-Sin, king, built the temple of Shara in Umm

It is well known from later periods that the making of divine statues was a very religious work, not simply craftsmanship, and this takes up back to Sumerian times. Though we have translated the Sumerian alam as “statue”, as it often is, it can also be “statuette”, and it may have been made of stone, wood, ivory or metal, but the mention of three metal workers suggests here metal, at least for the most of the body.

Cuneiform was used on monuments dedicated to heroic – and usually royal – individuals, but perhaps its most important function was that of record keeping. The palace-based society at Ur and other large urban centres was accompanied by a remarkably complex and multifaceted bureaucracy, which was run by professional administrators and a priestly class, all of whom were answerable to central court control. Most of what we know about the way the culture was run and administered comes from cuneiform tablets, which record the everyday running of the temple and palace complexes in minute detail, as in the present case. The Barakat Gallery has secured the services of Professor Lambert (University of Birmingham), a renowned expert in the decipherment and translation of cuneiform, to examine and process the information on these tablets. His scanned analysis is presented here. This is an extremely rare text recording the making of a statue of the third king of the Ur dynasty, Amar-Suena. Kings were accorded divine status in Sumerian society and this may be the reason for the present document.

Professor Lambert’s translation is provided below:

Clay tablet, 62x47mm., with a total of 17 lines of Sumerian cuneiform on obverse and reverse. An administrative document from the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur, dated to the 9th year of Shu-Sin, fourth king of the dynasty, c. 2029 B.C. It is a rare and important tablet, and it is thus all the more to be regretted that not everything can be read. The scribe rolled the surface of the tablet with his cylinder seal after he ad written it, and in doing so obscured many of the signs. In addition there is some surface corrosion and one rejoined patch. The obverse is most affected, the reverse much less so. The tablet is a record of the making of a statue of the third king of the dynasty, Amar-Suena, father of the then reigning king. It is well known that these kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur were accorded divine status even in their lifetimes, and this may be the reason for the present document:

Translatio

2 . . . .

5 carpenter

1 leather worker: for 1 day to make a statue of the . . . king in the . . . templ

When they took the statue of Amar-Suena fom the inspection podium to the . . . temple, it was thanks to Puta-padda, thanks to Lu-Ninshuburaka and thanks to Nanna-dalla, metal workers of the kin

Month: barley harves

Year: Shu-Sin, king, built the temple of Shara in Umm

It is well known from later periods that the making of divine statues was a very religious work, not simply craftsmanship, and this takes up back to Sumerian times. Though we have translated the Sumerian alam as “statue”, as it often is, it can also be “statuette”, and it may have been made of stone, wood, ivory or metal, but the mention of three metal workers suggests here metal, at least for the most of the body.