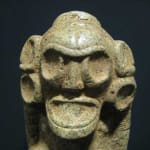

Taino Stone Zemi Sculpture, 1000 CE - 1500 CE

Stone

8 x 15.8

LK.053

This remarkable sculpture of a zemi figure is carved from a pale green/brown stone. A zemi was the physical manifestation of a Taino god, spirit or ancestor. As chieftains and...

This remarkable sculpture of a zemi figure is carved from a pale green/brown stone. A zemi was the physical manifestation of a Taino god, spirit or ancestor. As chieftains and important shamans were deified after death it may even represent a high status member of the Taino community. The arrangement of the figure’s limbs is extraordinary and is an elaboration of the ritual squatting position that zemis assume in surviving stone amulets. In this example the legs are bent at the knees with the feet facing inwards at an improbable angle. The hands rest on the knees with the fingers pointing downwards. The figure is naked except for two elaborate armbands just below the shoulders. Both the face and the body are skeletal in appearance with prominent hollow joints. The wide eye-sockets and gaping jaw are deeply carved and both the forehead and the chin project outwards at a sharp angle. The head has a round protrusion above the forehead, incised with geometric motifs. Perhaps the most striking features however are the large ears, formed from two deeply carved circular roundels on each side.

To western sensibilities there is an obvious contradiction between the figure’s skeletal form, suggestive of death and decay, and the fleshy, erect phallus visible between the knees. The latter is clearly a symbol of potency and fertility that seems oddly juxtaposed with bodily indicators of old age. However it was not unusual in the New World to combine such iconography. Parallels have been drawn with the pottery vessels from the ancient Moche civilization of Peru, which depict well-built women in the company of skeletal males with erect phalluses. As Peter Roe has argued, ‘In the New World, the iconography of mortality was linked to images of fecundity.’

A carving of this complexity and size must have belonged to a chieftain or member of his retinue. Although the Taino left no written records, the Spanish settlers did record native practices (though they did not necessarily understand their significance). One eye-witness refers to special structures or temples in which the chieftains stored their zemi carvings. The Taino believed in the existence of an afterlife and the ability of shamans to communicate with the dead. This sculpture may well have been a prop in such a ceremony, or a focus for ancestor worship. This is a remarkably evocative work that allows us to glimpse some of the splendours of Taino civilization. (AM)

To western sensibilities there is an obvious contradiction between the figure’s skeletal form, suggestive of death and decay, and the fleshy, erect phallus visible between the knees. The latter is clearly a symbol of potency and fertility that seems oddly juxtaposed with bodily indicators of old age. However it was not unusual in the New World to combine such iconography. Parallels have been drawn with the pottery vessels from the ancient Moche civilization of Peru, which depict well-built women in the company of skeletal males with erect phalluses. As Peter Roe has argued, ‘In the New World, the iconography of mortality was linked to images of fecundity.’

A carving of this complexity and size must have belonged to a chieftain or member of his retinue. Although the Taino left no written records, the Spanish settlers did record native practices (though they did not necessarily understand their significance). One eye-witness refers to special structures or temples in which the chieftains stored their zemi carvings. The Taino believed in the existence of an afterlife and the ability of shamans to communicate with the dead. This sculpture may well have been a prop in such a ceremony, or a focus for ancestor worship. This is a remarkably evocative work that allows us to glimpse some of the splendours of Taino civilization. (AM)