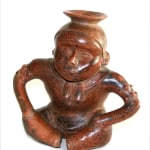

Colima Hunchback Vessel, 300 BCE - 300 CE

Terra Cotta

9.75

DB.027 (LSO)

Further images

This poignant and well-executed portrait representation of a hunchback was made at the end of the first millennium BC to the early days of the first millennium AD. The subgroup...

This poignant and well-executed portrait representation of a hunchback was made at the end of the first millennium BC to the early days of the first millennium AD. The subgroup that manufactured the piece are called the Colima, who are part of a group of archaeological cultures – known almost purely from their artworks – referred to as the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb (WMST) tradition. There are many distinct groups within this agglomeration, and their relationships are almost totally obscure due to the lack of contextual information. However, it is the artworks that are the most informative, as we can see from the current piece.

The vessel would seem to be somewhat impractical, for although it was doubtless able to hold liquids (probably maize beer) it is likely to have had another function, probably votive, funerary or ritual. Its most valuable aspect, however, is in what it represents. The body of the vessel is a seated male adult, hunched over and supporting his weight on his hands, pressed against his thighs. His face is a study in passivity, with stark cheekbones, a rounded forehead, an angular nose and small lips, dominated by curiously blank eyes with hooded lids. He is seemingly nude, with a cloth cap, armbands around each bicep and a double amulet strung around his neck on a thong. His limbs are somewhat nugatory, their detail minimised in order to attract attention to the sculpture’s solid core. In frontal view, this would seem to be the subtotal of his characteristics, yet his lateral and posterior view reveal a massive hunchback formation from just below the shoulders to the mid-spine.

The deformity is a classical angular kyphosis, with the bodies of muscle on the shoulders rising above the midline of the spine. The detailing is merciless in its exactitude; it is clearly the most important aspect of the sculpture in the eyes of its creator. The significance of this pathology is discussed after a short summary of the culture that produced it.

All of the cultures encompassed under the WMST nomenclature were in the habit of burying their dead in socially-stratified burial chambers at the base of deep shafts, which were in turn often topped by buildings. Originally believed to be influenced by the Tarascan people, who were contemporaries of the Aztecs, thermoluminescence has pushed back the dates of these groups over 1000 years. Although the apogee of this tradition was reached in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BC, it has its origins over 1000 years earlier at sites such as Huitzilapa and Teuchitlan, in the Jalisco region. Little is known of the cultures themselves, although preliminary data seems to suggest that they were sedentary agriculturists with social systems not dissimilar to chiefdoms. These cultures are especially interesting to students of Mesoamerican history as they seem to have been to a large extent outside the ebb and flow of more aggressive cultures – such as the Toltecs, Olmecs and Maya – in the same vicinity. Thus insulated from the perils of urbanisation, they developed very much in isolation, and it behoves us to learn what we can from what they have left behind.

The arts of this region are enormously variable and hard to understand in chronological terms, mainly due to the lack of context. The most striking works are the ceramics, which were usually placed in graves, and do not seem to have performed any practical function (although highly decorated utilitarian vessels are also known). It is possible that they were designed to depict the deceased – they are often very naturalistic – although it is more probable that they constituted, when in groups, a retinue of companions, protectors and servants for the hereafter. More abstract pieces – such as reclinatorios – probably had a more esoteric meaning that is hard to recapture from the piece.

The current piece falls within the Colima style, which is perhaps the most unusual stylistic subgroup of this region. Characterised by a warm, red glaze, the figures are very measured and conservative, while at the same time displaying a great competence of line. They are famous for their sculptures of obese dogs, which seem to have been fattened for the table. Colima reclinatorios are also remarkable, curvilinear yet geometric assemblages of intersecting planes and enigmatic constructions in the semi-abstract. The current piece, however, is in many respects more socially valuable than the aforementioned, as it portrays not only naturalistic aspects of Colima lifestyle, but also something of the nature of their society.

There are various conditions that can bring about angular kyphosis (a slumping forward) or scoliosis (slumping/twisting to the side) of the spine. They can be genetic, or be the result of old age – associated with conditions such as osteoporosis. However, by far the most important cause is tuberculosis. This disease is endemic in the Americas, and the earliest examples predate most European cases. The likelihood that this disease caused the kyphosis in the current case is increased by the rather sunken appearance of the cheeks in relation to the face, and the boniness of the nose and jawline. One might logically enquire as to why a sick person would have been portrayed at all, but in fact there was less stigma attached to illness and infirmity in many American societies than subsequent (and western) groups. They were even revered in various populations, perhaps because of their “comic” appearance, but also perhaps because they had survived a disease that was usually fatal; their survival must have been a miraculous thing indeed. The Moche of northern Peru also depicted the infirm, from hunchbacks to lepers, syphilitics, amputees and the mutilated – it is believed that these acted as cautionary tales. The status of this individual is evident in his scarce yet informative apparel; from what little we know of these cultures, such items were reserved for cultural elites, so the person depicted must have been important despite – or even, perhaps, because of – his illness.

This is a stirring and fascinating piece of ancient American art.

The vessel would seem to be somewhat impractical, for although it was doubtless able to hold liquids (probably maize beer) it is likely to have had another function, probably votive, funerary or ritual. Its most valuable aspect, however, is in what it represents. The body of the vessel is a seated male adult, hunched over and supporting his weight on his hands, pressed against his thighs. His face is a study in passivity, with stark cheekbones, a rounded forehead, an angular nose and small lips, dominated by curiously blank eyes with hooded lids. He is seemingly nude, with a cloth cap, armbands around each bicep and a double amulet strung around his neck on a thong. His limbs are somewhat nugatory, their detail minimised in order to attract attention to the sculpture’s solid core. In frontal view, this would seem to be the subtotal of his characteristics, yet his lateral and posterior view reveal a massive hunchback formation from just below the shoulders to the mid-spine.

The deformity is a classical angular kyphosis, with the bodies of muscle on the shoulders rising above the midline of the spine. The detailing is merciless in its exactitude; it is clearly the most important aspect of the sculpture in the eyes of its creator. The significance of this pathology is discussed after a short summary of the culture that produced it.

All of the cultures encompassed under the WMST nomenclature were in the habit of burying their dead in socially-stratified burial chambers at the base of deep shafts, which were in turn often topped by buildings. Originally believed to be influenced by the Tarascan people, who were contemporaries of the Aztecs, thermoluminescence has pushed back the dates of these groups over 1000 years. Although the apogee of this tradition was reached in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BC, it has its origins over 1000 years earlier at sites such as Huitzilapa and Teuchitlan, in the Jalisco region. Little is known of the cultures themselves, although preliminary data seems to suggest that they were sedentary agriculturists with social systems not dissimilar to chiefdoms. These cultures are especially interesting to students of Mesoamerican history as they seem to have been to a large extent outside the ebb and flow of more aggressive cultures – such as the Toltecs, Olmecs and Maya – in the same vicinity. Thus insulated from the perils of urbanisation, they developed very much in isolation, and it behoves us to learn what we can from what they have left behind.

The arts of this region are enormously variable and hard to understand in chronological terms, mainly due to the lack of context. The most striking works are the ceramics, which were usually placed in graves, and do not seem to have performed any practical function (although highly decorated utilitarian vessels are also known). It is possible that they were designed to depict the deceased – they are often very naturalistic – although it is more probable that they constituted, when in groups, a retinue of companions, protectors and servants for the hereafter. More abstract pieces – such as reclinatorios – probably had a more esoteric meaning that is hard to recapture from the piece.

The current piece falls within the Colima style, which is perhaps the most unusual stylistic subgroup of this region. Characterised by a warm, red glaze, the figures are very measured and conservative, while at the same time displaying a great competence of line. They are famous for their sculptures of obese dogs, which seem to have been fattened for the table. Colima reclinatorios are also remarkable, curvilinear yet geometric assemblages of intersecting planes and enigmatic constructions in the semi-abstract. The current piece, however, is in many respects more socially valuable than the aforementioned, as it portrays not only naturalistic aspects of Colima lifestyle, but also something of the nature of their society.

There are various conditions that can bring about angular kyphosis (a slumping forward) or scoliosis (slumping/twisting to the side) of the spine. They can be genetic, or be the result of old age – associated with conditions such as osteoporosis. However, by far the most important cause is tuberculosis. This disease is endemic in the Americas, and the earliest examples predate most European cases. The likelihood that this disease caused the kyphosis in the current case is increased by the rather sunken appearance of the cheeks in relation to the face, and the boniness of the nose and jawline. One might logically enquire as to why a sick person would have been portrayed at all, but in fact there was less stigma attached to illness and infirmity in many American societies than subsequent (and western) groups. They were even revered in various populations, perhaps because of their “comic” appearance, but also perhaps because they had survived a disease that was usually fatal; their survival must have been a miraculous thing indeed. The Moche of northern Peru also depicted the infirm, from hunchbacks to lepers, syphilitics, amputees and the mutilated – it is believed that these acted as cautionary tales. The status of this individual is evident in his scarce yet informative apparel; from what little we know of these cultures, such items were reserved for cultural elites, so the person depicted must have been important despite – or even, perhaps, because of – his illness.

This is a stirring and fascinating piece of ancient American art.