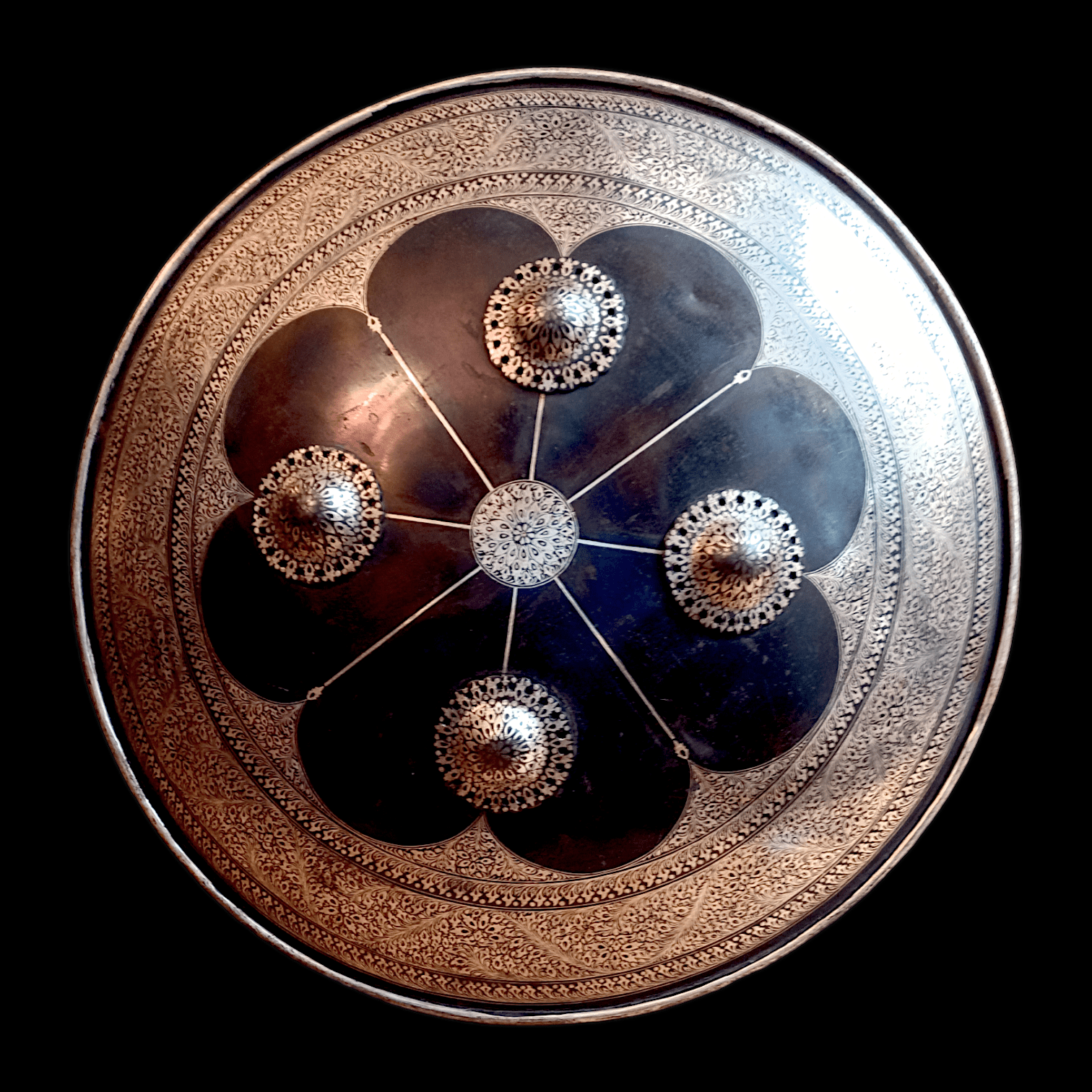

Qajar-Era Indo-Persian Engraved Shield (Dhal), with Four Bosses, Eighteenth to Nineteenth Century AD

Black Steel, Silver

6.9 x 50.4 cm

2 3/4 x 19 7/8 in

2 3/4 x 19 7/8 in

CC.361

The round shield was something of a revolution in warfare. The rectangular shield, sometimes called a ‘tower shield’, might have been great for covering as much of the body as...

The round shield was something of a revolution in warfare. The rectangular shield, sometimes called a ‘tower shield’, might have been great for covering as much of the body as possible, but they reduced manoeuvrability significantly. This was fine if soldiers were lined up in neat static rows ready for the next attack – indeed, the Roman Army was famed for such tactics, and used them to great effect – it was a hindrance in the fast-moving context of a cavalry or chariot battle. While smaller, and therefore less effective against unpredictable attacks like a volley of arrows, the round shield kept the legs free for movement, provided better frontal vision, and gave more angles at which one could swing one’s sword. First introduced in the Bronze Age, the idea was taken up most successfully by the Ancient Greeks, whose hoplites (armoured spearmen, named for their round shield, the hoplos) dominated the Eastern Mediterranean from the Sixth to the Fourth Centuries BC. Despite being famed for their rectangular shields (scutae), the Romans nonetheless used rounded shields (clipei) during the Republican Era, and eventually hybridised rounded and rectangular elements into the ovoid parma, which had a smaller circular cousin (the parmula), in the Third Century AD. Successful Norse warriors, Scottish rebels, Mediaeval knights, and myriad others also used round shields. But perhaps their greatest development occurred in South Asia and the Middle East.

The dhal, an Indian round shield with four bosses, was a development of the Tenth or Eleventh Century AD, originating in Assam, and later associated with Sikh warriors. The four bosses served multiple purposes. Foremost, they secure the handle-straps of the shield, capping the bolt or hook which passes through the metal surface such that the protective surface of the shield remains unbroken. Additionally, they provide points of strength on the shield, which could be used to push back against the enemy, or even as an offensive blunt weapon to startle one’s opponent. And the bosses help to deflect oblique blows: a sword being swung along the surface of the shield, perhaps upwards towards the bearer’s face, or downwards towards his knees, would catch on the bosses, thus preventing nasty injury. Dhal, technically a kind of buckler (small round shield to be held in the fist to parry blows), had a larger cousin known as a baru. Both were originally made from animal hide – usually from the water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), but occasionally from the rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) – but later wooden and metal versions predominated, especially among the ceremonial examples. One particularly ornate ceremonial dhal, made with over eight hundred diamonds, was presented to the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, during his tour of India in AD 1875 (Royal Collection Trust 11278).

Islamic exposure to the dhal design occurred under the Mughal rulers of India, whose founder, Babur (reigned AD 1526 – AD 1530), was a Central Asian of Timurid descent. The design coincided with, and was merged with, another of Ottoman Turkish origin, the kalkan, originally made from wickerwork within an iron or steel frame, and with a large central boss. The innovation of multiple bosses, against which the blows of a sword could be deflected, was enthusiastically taken up by the Persian weapon-smiths, who began producing dhal-kalkan hybrids in their workshops. This shield follows such a pattern. Measuring 50.4 cm (19 7/8 in) in diameter, it is towards the upper end of the usual range for dhal shields, which range from 20 cm (7 7/8 in; a so-called buckler, for deflecting sword-blows in close hand-to-hand combat) to a more substantial 61 cm (24 in). The four solid bosses, which protrude a good 2 cm (1 in) from the surface of the shield, are solid, and are ringed with a radiate motif which mimics the rays of the sun, or else the petals of sunflowers. An important crop in Iran, and a healthy source of oil which could be used not only for cooking, but also lighting lamps, sunflowers (Helianthus annus) were symbolic both of rebirth and of the shining face of the Ahura-Mazda, the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian deity of the sky, whose significance in Iran was fossilised in folk tradition. The petal motif is mimicked in the central pattern of the shield, which radiates from the centre-point. These petals mimic the shape of boteh, the Persian teardrop-shaped cartouches which predominantly decorated fabrics. The dark colour of the metal, known as black steel, originates in the high proportion of iron in the steel’s fabric, which oxidises and turns black in high-temperature charcoal firing. The surface is damascened, a process named after the city of Damascus where it was invented. The elaborate arabesques of swirling foliate elements, were carved by hand into the surface of the steel, and then silver wire placed over the positive space. When heated, the silver pooled in the troughs of the carving, and when smoothed provides a remarkably rich decorative surface. Silver, rare in Iran, was more valuable than gold for much of Persian history.

This shield is certainly a parade piece, designed to impress foreign dignitaries, and indeed one another. The Qajar military was made up both of regular forces, under the direct control of the monarch, and irregular tribal detachments which provided potentially dangerous alternative loci of power. It was as important that the various commanders of these forces impressed one another, to establish their own legitimacy, as it was to impress the European and other foreign powers whose empires were reshaping the global balance of power, and who were fascinated by the irredeemable exoticism of sword-and-shield-wielding warriors in a world of increasing mechanisation of warfare.

The dhal, an Indian round shield with four bosses, was a development of the Tenth or Eleventh Century AD, originating in Assam, and later associated with Sikh warriors. The four bosses served multiple purposes. Foremost, they secure the handle-straps of the shield, capping the bolt or hook which passes through the metal surface such that the protective surface of the shield remains unbroken. Additionally, they provide points of strength on the shield, which could be used to push back against the enemy, or even as an offensive blunt weapon to startle one’s opponent. And the bosses help to deflect oblique blows: a sword being swung along the surface of the shield, perhaps upwards towards the bearer’s face, or downwards towards his knees, would catch on the bosses, thus preventing nasty injury. Dhal, technically a kind of buckler (small round shield to be held in the fist to parry blows), had a larger cousin known as a baru. Both were originally made from animal hide – usually from the water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), but occasionally from the rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) – but later wooden and metal versions predominated, especially among the ceremonial examples. One particularly ornate ceremonial dhal, made with over eight hundred diamonds, was presented to the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, during his tour of India in AD 1875 (Royal Collection Trust 11278).

Islamic exposure to the dhal design occurred under the Mughal rulers of India, whose founder, Babur (reigned AD 1526 – AD 1530), was a Central Asian of Timurid descent. The design coincided with, and was merged with, another of Ottoman Turkish origin, the kalkan, originally made from wickerwork within an iron or steel frame, and with a large central boss. The innovation of multiple bosses, against which the blows of a sword could be deflected, was enthusiastically taken up by the Persian weapon-smiths, who began producing dhal-kalkan hybrids in their workshops. This shield follows such a pattern. Measuring 50.4 cm (19 7/8 in) in diameter, it is towards the upper end of the usual range for dhal shields, which range from 20 cm (7 7/8 in; a so-called buckler, for deflecting sword-blows in close hand-to-hand combat) to a more substantial 61 cm (24 in). The four solid bosses, which protrude a good 2 cm (1 in) from the surface of the shield, are solid, and are ringed with a radiate motif which mimics the rays of the sun, or else the petals of sunflowers. An important crop in Iran, and a healthy source of oil which could be used not only for cooking, but also lighting lamps, sunflowers (Helianthus annus) were symbolic both of rebirth and of the shining face of the Ahura-Mazda, the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian deity of the sky, whose significance in Iran was fossilised in folk tradition. The petal motif is mimicked in the central pattern of the shield, which radiates from the centre-point. These petals mimic the shape of boteh, the Persian teardrop-shaped cartouches which predominantly decorated fabrics. The dark colour of the metal, known as black steel, originates in the high proportion of iron in the steel’s fabric, which oxidises and turns black in high-temperature charcoal firing. The surface is damascened, a process named after the city of Damascus where it was invented. The elaborate arabesques of swirling foliate elements, were carved by hand into the surface of the steel, and then silver wire placed over the positive space. When heated, the silver pooled in the troughs of the carving, and when smoothed provides a remarkably rich decorative surface. Silver, rare in Iran, was more valuable than gold for much of Persian history.

This shield is certainly a parade piece, designed to impress foreign dignitaries, and indeed one another. The Qajar military was made up both of regular forces, under the direct control of the monarch, and irregular tribal detachments which provided potentially dangerous alternative loci of power. It was as important that the various commanders of these forces impressed one another, to establish their own legitimacy, as it was to impress the European and other foreign powers whose empires were reshaping the global balance of power, and who were fascinated by the irredeemable exoticism of sword-and-shield-wielding warriors in a world of increasing mechanisation of warfare.