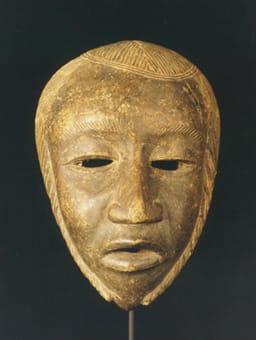

Bambara Wooden Mask, 20th Century CE

Wood

18.3 x 27.9 cm

7 1/4 x 11 in

7 1/4 x 11 in

PF.4431 (LSO)

This striking mask was made by the Bambara/Bamana people of Mali. The face shape is unusual, being broader than is conventional, as well as being more paedomorphic and naturalistic. The...

This striking mask was made by the Bambara/Bamana people of Mali. The face shape is unusual, being broader than is conventional, as well as being more paedomorphic and naturalistic. The face is broad-browed, narrowing to full cheeks and a pointed chin. The whole is encircled with hair – braids by the side of the face and hatched incised asymmetrical coiffure superiorly. The quality of the rendering is very high, with the subtle slow and ebb of facial contours picked out in exquisite detail. The sensitivity of the lips and cheeks is exceptional. The high quality of the carving is accentuated by the beautiful glossy use patina.

The Bambara/Bamana are one of the largest groups in Mali (about 2.5 million) and lives in a savannah grassland area that contrasts strongly with the Dogon heartland. Their linguistic heritage indicates that they are part of the Mande group, although their origins go back perhaps as far as 1500 BC in the present-day Sahara. They gave rise to the Bozo, who founded Djenne in an area subsequently overrun by the Soninke Mande (<1100 AD). Their last empire dissolved in the 1600s, and many Mande speakers spread out along the Nigeria River Basin. The Bamana empire arose from these remnant populations in around 1740. The height of its imperial strength was reached in the 1780s under the rule of Ngolo Diarra, who expanded their territory considerably.

Their society is Mande-like overall, with patrilineal descent and a nobility/vassal caste system that is further divided into numerous subvariants including the Jula (traders), Fula (cattle herding), Bozo (indentured slaves) and Maraka (rich merchants). Age, sex and occupation groups are classed to reflect their social importance. This complex structure is echoed in the systematics of indigenous art traditions. Sculptures include Guandousou, Guaitigi and Guanyenni figures – that are used to promote fertility and social balance – while heavily encrusted zoomorphic Boli figures serve an apotropaic function, and curvaceous dyonyeni sculptures are used in initiation ceremonies. Everyday items include iron staffs, wooden puppets and equestrian figures; their sexually-constructed anthropomorphic door locks are especially well-known. There are four main mask forms. The N’tomo society has the best-known form, with a tall, face topped by a vertical comb structure. The Komo society uses an elongated, demonic-looking mask with various animal parts arranged into a fearsome zoomorphic form that is worn atop the head. The Nama society uses a mask that is based around an articulated bird’s head, while the little-known Kore rituals involve a deconstructed animal head. Members of the Jo and Gwan societies are also believed to have worn such pieces, but the exact systematic are not fully understood. Chiwara headcrests – which represent deconstructed antelopes – are distinct creations, and as such are usually considered separately.

This mask, however, poses something of a quandary as it does match any of these descriptions. In crude terms, it is perhaps most like the N’tomo society mask as it is a human face, and not an animal or a bird, or abstracted. Likewise, the Gwan and Jo societies have their own somewhat secret masks, and the full variability of mask production in pre-contact Bambara society is yet something of a mystery. What is certain, however, is that many Bambara masks are made with function as a main priority, and this mask is evidence that their aesthetic potentialities were genuinely superb. This is an exceptionally beautiful mask, which would be a great addition to any serious collection.

The Bambara/Bamana are one of the largest groups in Mali (about 2.5 million) and lives in a savannah grassland area that contrasts strongly with the Dogon heartland. Their linguistic heritage indicates that they are part of the Mande group, although their origins go back perhaps as far as 1500 BC in the present-day Sahara. They gave rise to the Bozo, who founded Djenne in an area subsequently overrun by the Soninke Mande (<1100 AD). Their last empire dissolved in the 1600s, and many Mande speakers spread out along the Nigeria River Basin. The Bamana empire arose from these remnant populations in around 1740. The height of its imperial strength was reached in the 1780s under the rule of Ngolo Diarra, who expanded their territory considerably.

Their society is Mande-like overall, with patrilineal descent and a nobility/vassal caste system that is further divided into numerous subvariants including the Jula (traders), Fula (cattle herding), Bozo (indentured slaves) and Maraka (rich merchants). Age, sex and occupation groups are classed to reflect their social importance. This complex structure is echoed in the systematics of indigenous art traditions. Sculptures include Guandousou, Guaitigi and Guanyenni figures – that are used to promote fertility and social balance – while heavily encrusted zoomorphic Boli figures serve an apotropaic function, and curvaceous dyonyeni sculptures are used in initiation ceremonies. Everyday items include iron staffs, wooden puppets and equestrian figures; their sexually-constructed anthropomorphic door locks are especially well-known. There are four main mask forms. The N’tomo society has the best-known form, with a tall, face topped by a vertical comb structure. The Komo society uses an elongated, demonic-looking mask with various animal parts arranged into a fearsome zoomorphic form that is worn atop the head. The Nama society uses a mask that is based around an articulated bird’s head, while the little-known Kore rituals involve a deconstructed animal head. Members of the Jo and Gwan societies are also believed to have worn such pieces, but the exact systematic are not fully understood. Chiwara headcrests – which represent deconstructed antelopes – are distinct creations, and as such are usually considered separately.

This mask, however, poses something of a quandary as it does match any of these descriptions. In crude terms, it is perhaps most like the N’tomo society mask as it is a human face, and not an animal or a bird, or abstracted. Likewise, the Gwan and Jo societies have their own somewhat secret masks, and the full variability of mask production in pre-contact Bambara society is yet something of a mystery. What is certain, however, is that many Bambara masks are made with function as a main priority, and this mask is evidence that their aesthetic potentialities were genuinely superb. This is an exceptionally beautiful mask, which would be a great addition to any serious collection.