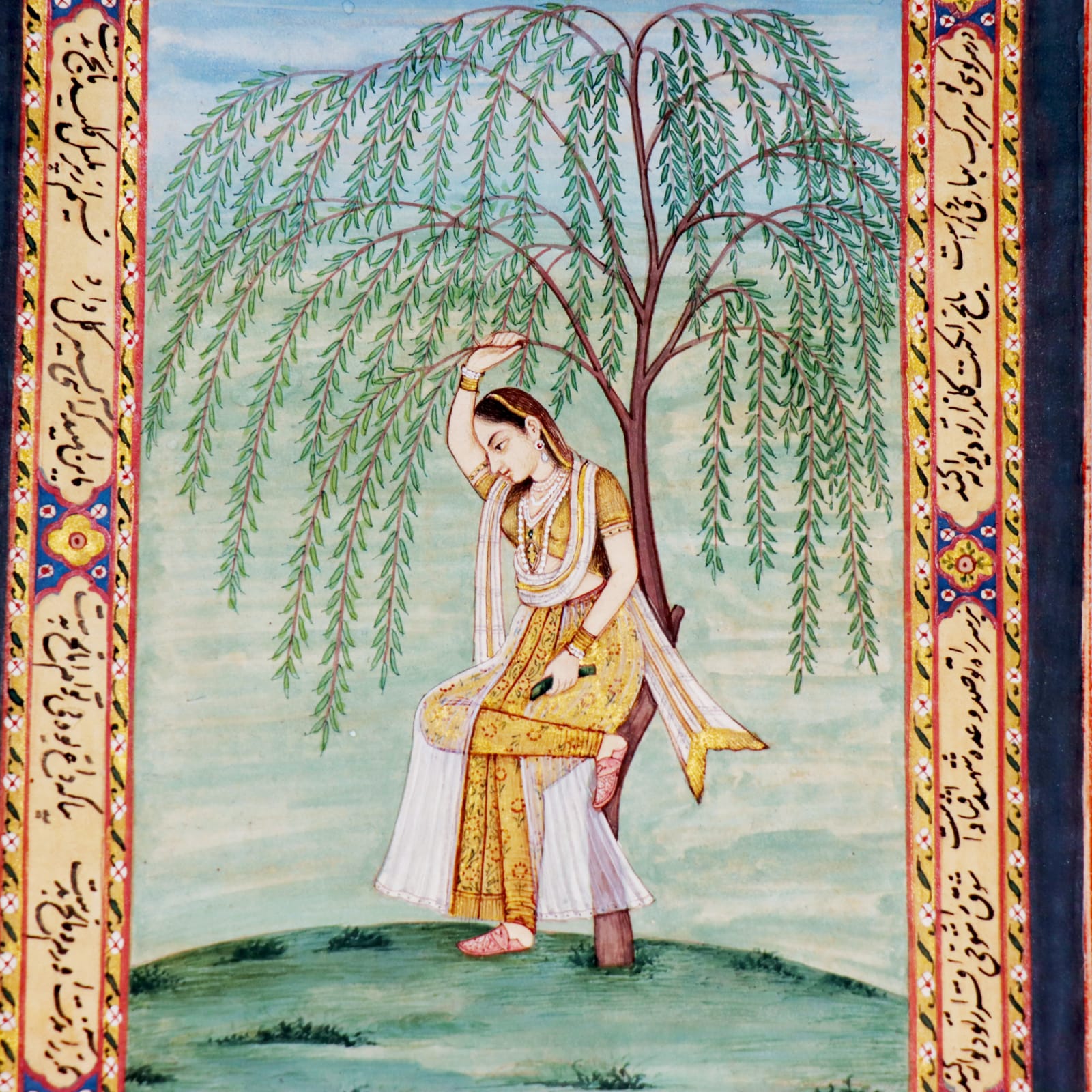

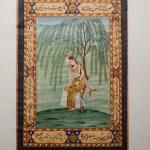

Mughal Miniature, depicting a Lovelorn Princess, Eighteenth to Nineteenth Century AD

Watercolour, Tempera, Ink, Gold Leaf, Paper

22.3 x 13.8 cm

8 3/4 x 5 3/8 in

8 3/4 x 5 3/8 in

CC.278

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 15

)

Introduced during the reign of the great Mughal Emperor Akbar (AD 1542 – AD 1605), miniature painting became the characteristic art-form of Mughal India. While the form itself was imported...

Introduced during the reign of the great Mughal Emperor Akbar (AD 1542 – AD 1605), miniature painting became the characteristic art-form of Mughal India. While the form itself was imported from Persia, it originally derived from Ming Dynasty China, where narrative painting on silk, wood and paper became hugely important, both as a vehicle through which to praise the Emperor, and as a mode of scholarly contemplation. The Mughal Imperial Court promoted a rigid and formal, though nonetheless expressive, style of painting, noted for its remarkable depiction of small details – the Damask roses (Rosa damascena) held to the noses of the Emperors, for example. In the regional courts of India, home to rajas, maharajas and princes (the so-called Princely States), a freer and more emotional mode of painting prevailed. Highly prized by the Europeans upon their gradual and piecemeal conquest of India, Mughal miniatures began to be produced for both a native and an export market, with themes adapted accordingly. Alongside historical and mythological scenes – from the Hindu as well as the Muslim tradition – and depictions of rulers and princes, Mughal miniatures also reflected the Indian taste in poetry and other forms of self-expression. The romantic, and even the erotic, were common subjects.

Romance is deeply rooted in Indian culture, and is commonly associated with the Mughal Period. Babur, the first Mughal Emperor, was well-known for his love poetry, which famously glorified women and raised themes such as lovesickness, homesickness and fidelity. His frank, and often revealing, poetry reveals an Emperor who misses his homeland in Central Asia – he cries, in one passage, at the sight of a melon from the region – who is torn apart at the loss of his family, and who experiences frequent and often taboo secret infatuations. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his poetry dedicated to his slave-boy Baburi, who he preferred to call Andijani. In one such poem, the Emperor writes: ‘may none be as I, humbled and wretched and lovesick; may no beloved be as pitiless and unconcerned as thou.’ The greatest monument of the Mughal Period, the Taj Mahal, has often been called a monument to love. Shah Jahan, the greatest of all the Mughal Emperors, was famously distraught when, in AD 1631, his wife Mumtaz Mahal died in childbirth. Ignoring the requirements of state, Jahan travelled through his vast Empire, until he came upon a tract of land to the south of Agra. Enamoured with its beauty, he chose that site to construct the Taj Mahal, a soaring masterpiece of white marble, to act as his wife’s mausoleum. Both Babur’s and Jahan’s stories reflect the theme of ghurbat, or exile, which was metaphorically applied to separation from one’s beloved. In Jahan’s case, the veil of life kept him from Mumtaz, while for Babur, social norms and Baburi’s obliviousness prevented the fulfilment of his longing.

The theme of separation from one’s beloved was also a common one for miniature paintings. This remarkable depiction represents just such a scene: a richly-clad woman, in a golden ensemble known as the ghagra choli. The garment is made up of three elements: the choli is a midriff-bearing blouse with short sleeves and a low neck; the ghagra is a long pleated skirt secured at the waist; and the dupatta is a scarf or shawl, which usually falls over the shoulders, and may be brought up over the head. This woman’s gaghra choli ensemble is of a rich golden hue, patterned with small flowers, while he dupatta is of a sheer white material, fringed with gold. Ghagra choli was a form of casual undress, usually worn under the sari, which informs us that this painting takes place in a private setting. It was predominantly worn by women in Rajasthan, as well as in Punjab, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, and in other regions straddling the modern India-Pakistan border. The woman’s expensive jewellery – pearl necklace, teardrop earrings, golden bangles – reveals her status, most likely as a princess in the minor royal families of north India. Her fair skin, slim physique, and delicate features, as well as her partly-covered lustrous raven hair, mark her out as a great beauty.

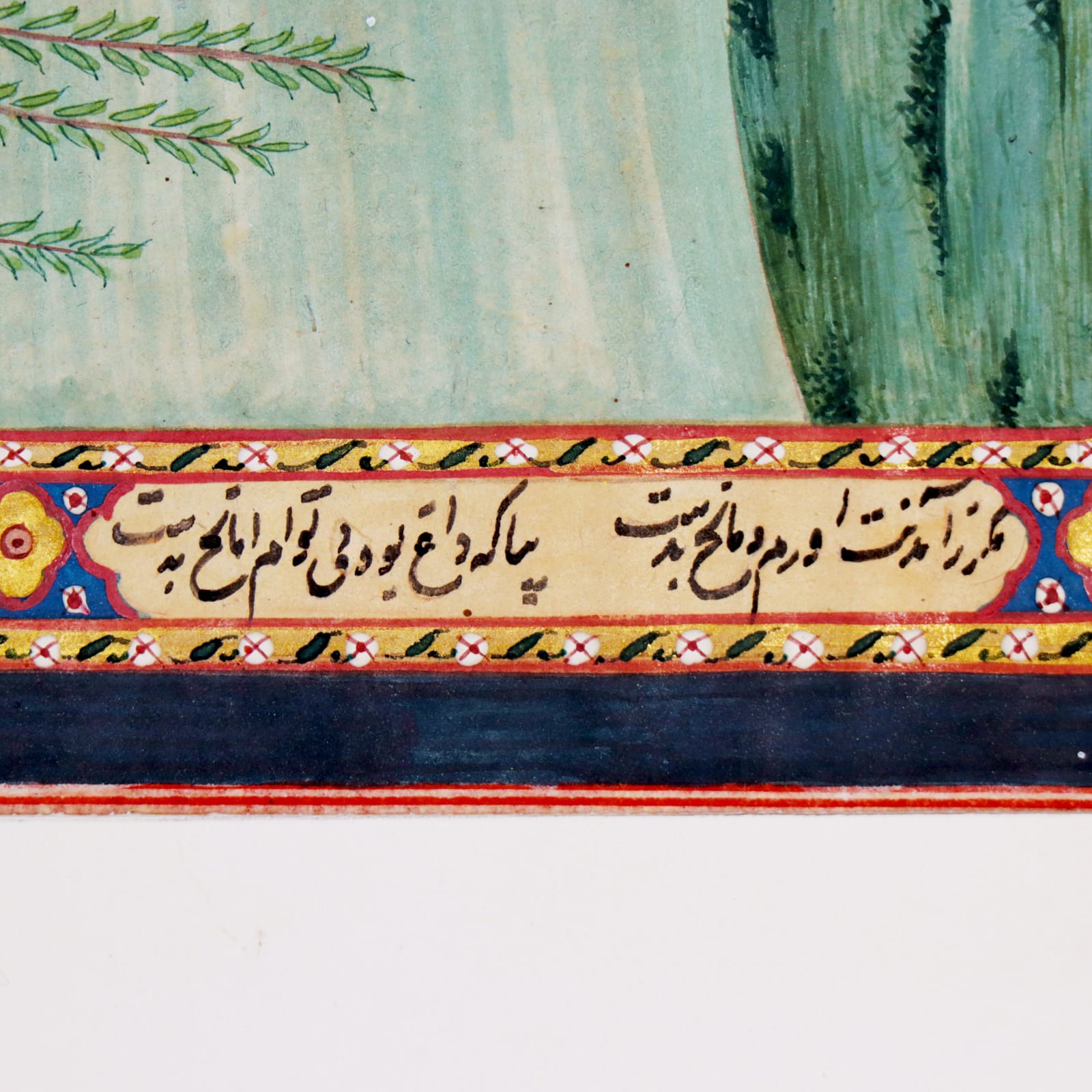

The woman stands in a garden – her attire tells us that it is a private garden – resting against a willow tree (Salix tetrasperma) sapling. Her pose is traditional, with one leg raised across her opposite knee as she rests, and the other foot firmly on the ground. She steadies herself with one of the willow’s dangling branches, and stares down at the ground. Her other hand clutches a green scroll to her waist. Her stance reflects earlier Hindu and Buddhist images of yakshini, female tree-nymphs (e.g. British Museum 1842,1210.1), an artistic motif known as salabhanjika. Her phenomenally expressive face reflects longing and disappointment; the scroll in her hand likely contains an unfulfilled promise from her lover to meet in the garden. Around the border of the piece are poetic couplets, rubai, a classical form of Persian and Urdu poetry. The style of the painting, and the attire of the figure, both suggest an origin in the Rajasthan regional school, one of India’s most productive centres for miniature painting.

References: miniatures of the same theme can be found in London (British Museum 1920,0917,0.115), Norwich (Sainsbury Centre 539), Lahore (Lahore Museum G-65), Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago 1926.717a).

Romance is deeply rooted in Indian culture, and is commonly associated with the Mughal Period. Babur, the first Mughal Emperor, was well-known for his love poetry, which famously glorified women and raised themes such as lovesickness, homesickness and fidelity. His frank, and often revealing, poetry reveals an Emperor who misses his homeland in Central Asia – he cries, in one passage, at the sight of a melon from the region – who is torn apart at the loss of his family, and who experiences frequent and often taboo secret infatuations. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his poetry dedicated to his slave-boy Baburi, who he preferred to call Andijani. In one such poem, the Emperor writes: ‘may none be as I, humbled and wretched and lovesick; may no beloved be as pitiless and unconcerned as thou.’ The greatest monument of the Mughal Period, the Taj Mahal, has often been called a monument to love. Shah Jahan, the greatest of all the Mughal Emperors, was famously distraught when, in AD 1631, his wife Mumtaz Mahal died in childbirth. Ignoring the requirements of state, Jahan travelled through his vast Empire, until he came upon a tract of land to the south of Agra. Enamoured with its beauty, he chose that site to construct the Taj Mahal, a soaring masterpiece of white marble, to act as his wife’s mausoleum. Both Babur’s and Jahan’s stories reflect the theme of ghurbat, or exile, which was metaphorically applied to separation from one’s beloved. In Jahan’s case, the veil of life kept him from Mumtaz, while for Babur, social norms and Baburi’s obliviousness prevented the fulfilment of his longing.

The theme of separation from one’s beloved was also a common one for miniature paintings. This remarkable depiction represents just such a scene: a richly-clad woman, in a golden ensemble known as the ghagra choli. The garment is made up of three elements: the choli is a midriff-bearing blouse with short sleeves and a low neck; the ghagra is a long pleated skirt secured at the waist; and the dupatta is a scarf or shawl, which usually falls over the shoulders, and may be brought up over the head. This woman’s gaghra choli ensemble is of a rich golden hue, patterned with small flowers, while he dupatta is of a sheer white material, fringed with gold. Ghagra choli was a form of casual undress, usually worn under the sari, which informs us that this painting takes place in a private setting. It was predominantly worn by women in Rajasthan, as well as in Punjab, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, and in other regions straddling the modern India-Pakistan border. The woman’s expensive jewellery – pearl necklace, teardrop earrings, golden bangles – reveals her status, most likely as a princess in the minor royal families of north India. Her fair skin, slim physique, and delicate features, as well as her partly-covered lustrous raven hair, mark her out as a great beauty.

The woman stands in a garden – her attire tells us that it is a private garden – resting against a willow tree (Salix tetrasperma) sapling. Her pose is traditional, with one leg raised across her opposite knee as she rests, and the other foot firmly on the ground. She steadies herself with one of the willow’s dangling branches, and stares down at the ground. Her other hand clutches a green scroll to her waist. Her stance reflects earlier Hindu and Buddhist images of yakshini, female tree-nymphs (e.g. British Museum 1842,1210.1), an artistic motif known as salabhanjika. Her phenomenally expressive face reflects longing and disappointment; the scroll in her hand likely contains an unfulfilled promise from her lover to meet in the garden. Around the border of the piece are poetic couplets, rubai, a classical form of Persian and Urdu poetry. The style of the painting, and the attire of the figure, both suggest an origin in the Rajasthan regional school, one of India’s most productive centres for miniature painting.

References: miniatures of the same theme can be found in London (British Museum 1920,0917,0.115), Norwich (Sainsbury Centre 539), Lahore (Lahore Museum G-65), Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago 1926.717a).