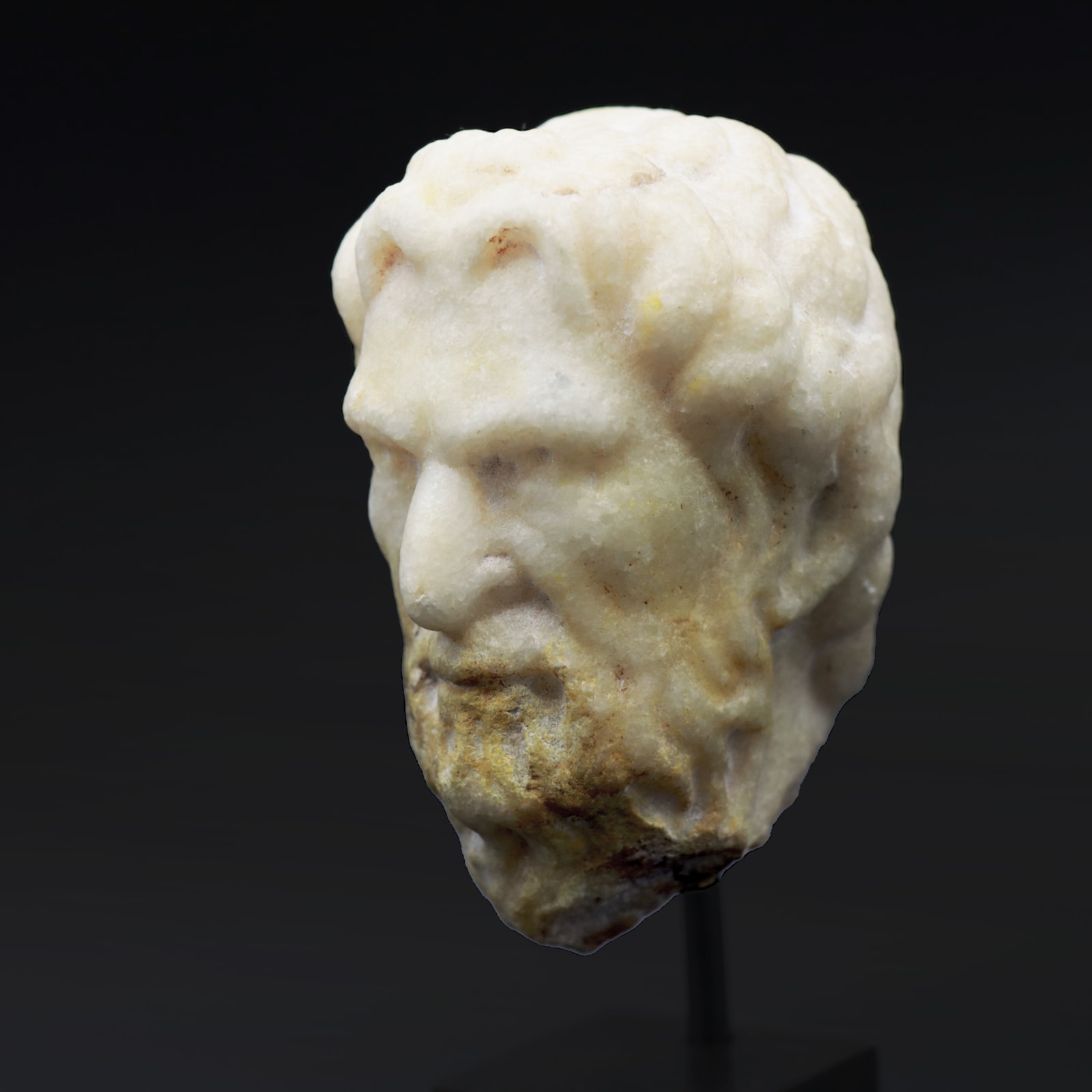

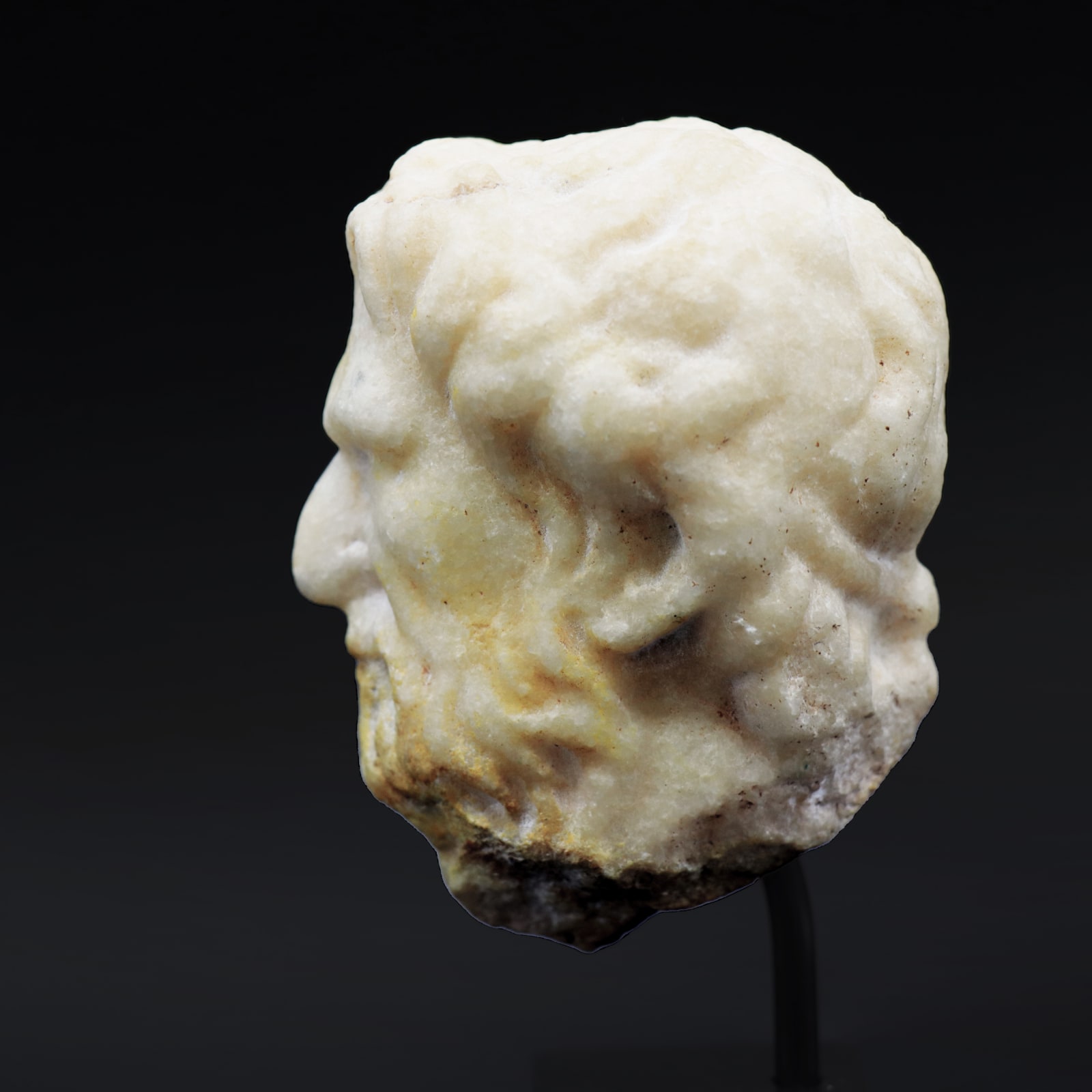

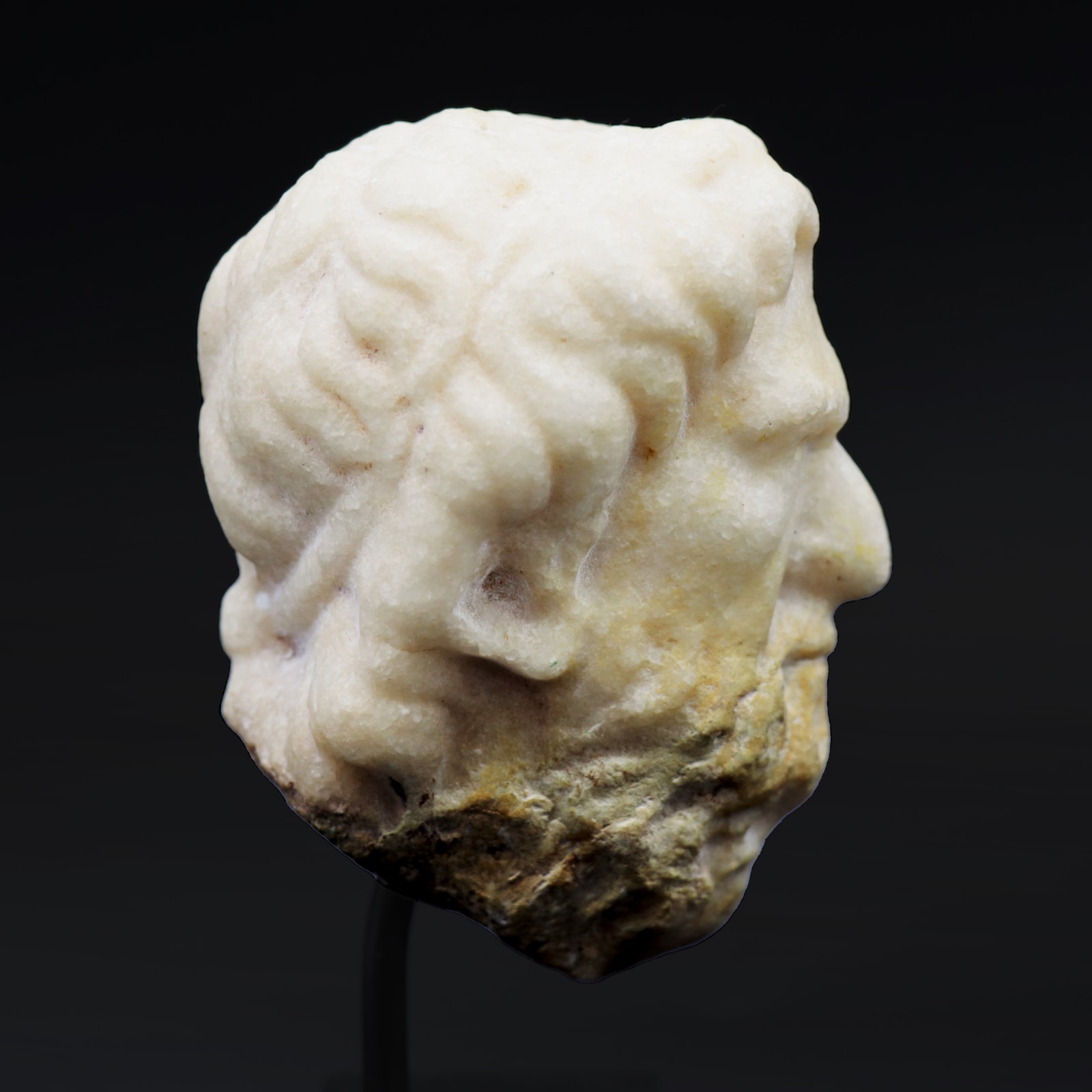

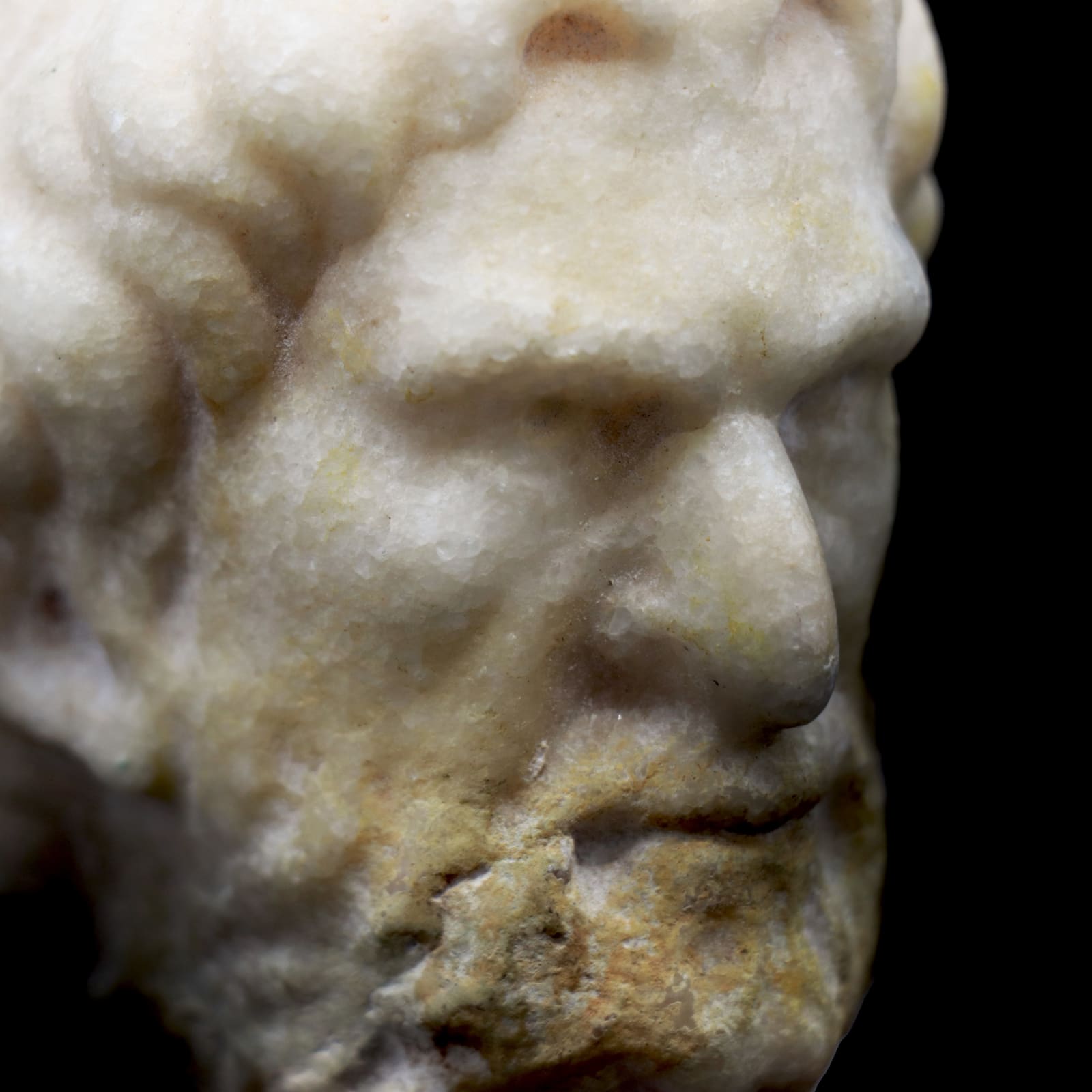

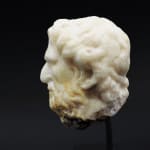

Portrait of an Antonine Emperor, possibly Antoninus Pius, AD 100 - AD 200

Marble

8 x 5.5 x 7.5 cm

3 1/8 x 2 1/8 x 3 in

3 1/8 x 2 1/8 x 3 in

CC.1

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

Historians tend to agree that one of the Roman Empire’s greatest difficulties was the variable quality of its Emperors. A lot of Emperors were, quite simply mad, bad, and dangerous...

Historians tend to agree that one of the Roman Empire’s greatest difficulties was the variable quality of its Emperors. A lot of Emperors were, quite simply mad, bad, and dangerous to know. The depravity of Caligula, Nero and Elagabalus was legendary, but it was their disregard for the administration of the Empire which was most damaging, alongside their inability to maintain Rome’s military might. Almost without exception, these bad Emperors met grizzly ends, usually at the hands of the Praetorian Guard who were tasked with protecting the Emperor’s person. However, just as the actions of bad Emperors damaged the Empire, there were certain rulers whose energy and activity were thought to have prolonged the Empire’s survival. Most revered were Rome’s first Emperor, Augustus, and those determined by Niccolò Machiavelli as the ‘five good Emperors’ (Machiavelli, N. () The Discourses on Livy. ). These leaders, Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, were credited with governing ‘by absolute power, under the guidance of wisdom and virtue’ (Gibbon, E. (1776) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Vol. 1, p. 78). The unusually peaceful reigns of these five Emperors, during which the Roman Empire was at its territorial peak, were looked back upon as an exemplar not only by later Romans, but also by succeeding generations of Europeans. Perhaps the greatest of these Emperors, or at least the one considered the most ‘good’, was Antoninus Pius.

The successor to the long and successful reign of the Emperor Hadrian, Antoninus Pius was born in the provincial town of Lanuvium, and could never have expected to take up the imperial purple. While his family were of relatively high rank, there was nothing that indicated that Antoninus would achieve such high office. This was, however, until his marriage around AD 110 to Faustina the Elder, a step-sister of Emperor Hadrian’s wife, Vibia Sabina. This strategic marriage propelled him into the imperial orbit. He was elected to the offices of quaestor (a low-ranking treasury official) and praetor (an official with broad authority), and exercised both roles with distinction. This brought him to Hadrian’s attention, and he obtained the consulship – broadly equivalent to a Prime Ministership – in AD 120. Once his consulship expired, he was appointed by Hadrian to govern northern Italy, and given other positions of trust in the imperial household. When Hadrian’s adopted son and successor, Lucius Aelius, died unexpectedly in AD 138, Hadrian appointed Antoninus as his successor. When Hadrian died later that year, Antoninus’ succession was not uncontroversial – there were numerous other rival claimants, including Lucius Catilius Severus – but the transition was generally peaceful. Antoninus’ first act was to convince the Senate to grant divine honours to Hadrian, which they were reluctant to do; this earnt him his nickname ‘Pius’, referring to his filial piety. His reign was marked by abnormal peace: it has been argued by some modern historians that Antoninus never went within 500 miles of a Roman legion, and he certainly never led an army in the field. Instead, he was particularly focused on domestic reform, expanding the Imperial Treasury, enfranchised freed slaves, and engaged in an extensive reform of the Roman legal system. During the peace of his reign, the Romans even embarked on their first diplomatic and trading mission to China. He died in AD 160, at the time the second-longest reigning Roman Emperor.

This remarkable portrait represents either Antoninus or one of his immediate successors; this much is certain from the gentle curl of the hairstyle, the presence of the beard, the aquiline nose, and the heavy brow. The prominent cheekbones and upward-looking eyes bear a striking resemblance to the portraits of Antoninus in the Vatican Museums (284.49), a damaged example in the Museo Nazionale Romano (108600), in the British Museum (1850,0116.1) and in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (33.11.3). The eyes have incised pupils, an innovation which occurred towards the end of Hadrian’s reign, helping us to date this portrait to the mid- to late-Second Century AD. The hair is held back from the forehead with a hairband or ribbon, visible at the rear of the statue. The ears are relatively large, another feature known from portraits of Antoninus. While this is a soft and sympathetic portrait, faithfully recreating the features of a dignified man in his fifties, there is a definite sternness and seriousness of expression, emphasised by the heavy brow. The contemplative expression is softened by a slight smile across the lips, and reinforces the gravitas of the emperor, imbuing him with a sense of dignity and sagacity.

References: portraits of Antoninus Pius with a similar heavy brow, aquiline nose, and prominent cheekbones, can be found in the Holy See (Musei Vaticani 284.49), Rome (Museo Nazionale Romano 108600), New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 33.11.3), and in London (British Museum 1850,0116.1).

The successor to the long and successful reign of the Emperor Hadrian, Antoninus Pius was born in the provincial town of Lanuvium, and could never have expected to take up the imperial purple. While his family were of relatively high rank, there was nothing that indicated that Antoninus would achieve such high office. This was, however, until his marriage around AD 110 to Faustina the Elder, a step-sister of Emperor Hadrian’s wife, Vibia Sabina. This strategic marriage propelled him into the imperial orbit. He was elected to the offices of quaestor (a low-ranking treasury official) and praetor (an official with broad authority), and exercised both roles with distinction. This brought him to Hadrian’s attention, and he obtained the consulship – broadly equivalent to a Prime Ministership – in AD 120. Once his consulship expired, he was appointed by Hadrian to govern northern Italy, and given other positions of trust in the imperial household. When Hadrian’s adopted son and successor, Lucius Aelius, died unexpectedly in AD 138, Hadrian appointed Antoninus as his successor. When Hadrian died later that year, Antoninus’ succession was not uncontroversial – there were numerous other rival claimants, including Lucius Catilius Severus – but the transition was generally peaceful. Antoninus’ first act was to convince the Senate to grant divine honours to Hadrian, which they were reluctant to do; this earnt him his nickname ‘Pius’, referring to his filial piety. His reign was marked by abnormal peace: it has been argued by some modern historians that Antoninus never went within 500 miles of a Roman legion, and he certainly never led an army in the field. Instead, he was particularly focused on domestic reform, expanding the Imperial Treasury, enfranchised freed slaves, and engaged in an extensive reform of the Roman legal system. During the peace of his reign, the Romans even embarked on their first diplomatic and trading mission to China. He died in AD 160, at the time the second-longest reigning Roman Emperor.

This remarkable portrait represents either Antoninus or one of his immediate successors; this much is certain from the gentle curl of the hairstyle, the presence of the beard, the aquiline nose, and the heavy brow. The prominent cheekbones and upward-looking eyes bear a striking resemblance to the portraits of Antoninus in the Vatican Museums (284.49), a damaged example in the Museo Nazionale Romano (108600), in the British Museum (1850,0116.1) and in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (33.11.3). The eyes have incised pupils, an innovation which occurred towards the end of Hadrian’s reign, helping us to date this portrait to the mid- to late-Second Century AD. The hair is held back from the forehead with a hairband or ribbon, visible at the rear of the statue. The ears are relatively large, another feature known from portraits of Antoninus. While this is a soft and sympathetic portrait, faithfully recreating the features of a dignified man in his fifties, there is a definite sternness and seriousness of expression, emphasised by the heavy brow. The contemplative expression is softened by a slight smile across the lips, and reinforces the gravitas of the emperor, imbuing him with a sense of dignity and sagacity.

References: portraits of Antoninus Pius with a similar heavy brow, aquiline nose, and prominent cheekbones, can be found in the Holy See (Musei Vaticani 284.49), Rome (Museo Nazionale Romano 108600), New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 33.11.3), and in London (British Museum 1850,0116.1).