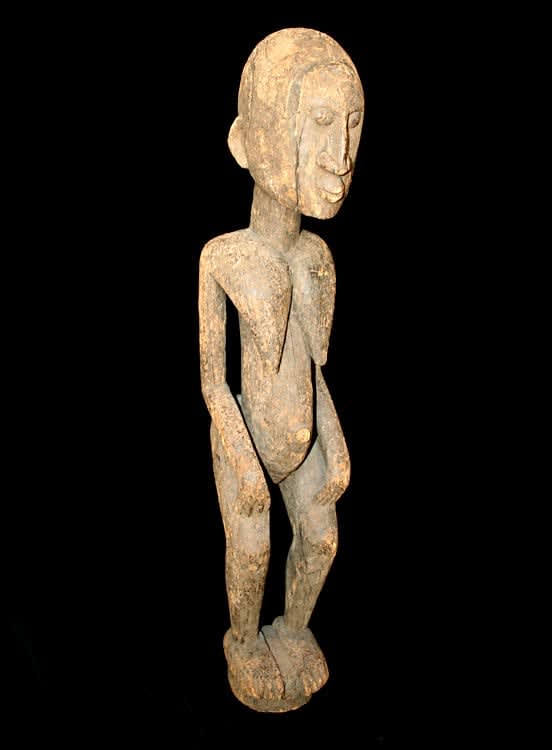

Dogon Female Figure, 19th Century CE - 20th Century CE

wood

height 90.2 cm

height 35 1/2 in

height 35 1/2 in

GDC.005 (LSO)

This tall and appealing piece is an ancestress sculpture made by the Dogon people of Mali. The rendering is slightly unusual. The legs are long, supporting a very curvilinear shape...

This tall and appealing piece is an ancestress sculpture made by the Dogon people of Mali. The rendering is slightly unusual. The legs are long, supporting a very curvilinear shape with a prominent abdomen and diving breasts that are part of the block comprising the shoulders. The legs leg is slightly raised, as if the figure was resting most of the weight on the right leg. The arms are long and the hands level with the waist. The neck is columnar, the head slightly oversized with a domed apes, small, rear-set ears and a strong yet serene face. The eyes are raised and rounded, the most crested and wide at the base. The mouth is small and also prominent. As a fairly large piece, it was probably a shrine figure.

The arms are also short, balancing what appears to be a pot on her coiffure. The breasts indicate that this is a mature woman, and the abdomen is swollen, perhaps indicating pregnancy. The patina is glossy and irregular.

The Dogon people of the Bandiagara escarpment, Mali, have been described as the most studied and least understood tribal group in Africa. Their culture is exceptionally complex, owing to their long history and also their internal variability along their home range. They moved to this area in the 15th century, escaping the Mande kingdom and slavery at the hands of Islamic groups, and displaced a number of tribes that were living on the escarpment at the time. They are excessively prolific in terms of artistic production; masks/figures in stone, iron, bronze/copper and of course wood are all known, in addition to cave/rock painting and adaptation of more modern materials. While Islam is prominent in and around the Dogon area, they have remained defiantly figurative in their artistic expression, a tradition which of course is technically banned under Islamic law.

There are seventy-eight different mask forms still in production (and numerous extinct variants), which have applications ranging from circumcision to initiation and funeral rites (damas). Some masks are only used once every sixty years (sigi funerary festivals), while others commemorate twins, snakes, ancestors (nommo) and hogons (holy men). Secular items – such as headrests, granary doors/locks and troughs – are decorated with iconographic designs that bestow benedictions upon the user or owner. Classification is also hampered by the large scale of the population and their homeland. The Dogon took inspiration from the Tellem (lit. “we found them”) sculptures recovered from caves on the escarpment, notably human figures with upraised arms in what is believed to be a prayer for rainfall. Most figures were not made to be seen publicly, and are commonly kept by the spiritual leader (hogon) away from the public eye, in family houses or sanctuaries.

It is not an understatement to claim that the Dogon are obsessed with their ancestors, both historical and mythical. This figure probably relates to a real or fictional ancestor, such as the semi-human nommo that feature at the very genesis of the Dogon people. This is a remarkable and imposing piece of African art.

The arms are also short, balancing what appears to be a pot on her coiffure. The breasts indicate that this is a mature woman, and the abdomen is swollen, perhaps indicating pregnancy. The patina is glossy and irregular.

The Dogon people of the Bandiagara escarpment, Mali, have been described as the most studied and least understood tribal group in Africa. Their culture is exceptionally complex, owing to their long history and also their internal variability along their home range. They moved to this area in the 15th century, escaping the Mande kingdom and slavery at the hands of Islamic groups, and displaced a number of tribes that were living on the escarpment at the time. They are excessively prolific in terms of artistic production; masks/figures in stone, iron, bronze/copper and of course wood are all known, in addition to cave/rock painting and adaptation of more modern materials. While Islam is prominent in and around the Dogon area, they have remained defiantly figurative in their artistic expression, a tradition which of course is technically banned under Islamic law.

There are seventy-eight different mask forms still in production (and numerous extinct variants), which have applications ranging from circumcision to initiation and funeral rites (damas). Some masks are only used once every sixty years (sigi funerary festivals), while others commemorate twins, snakes, ancestors (nommo) and hogons (holy men). Secular items – such as headrests, granary doors/locks and troughs – are decorated with iconographic designs that bestow benedictions upon the user or owner. Classification is also hampered by the large scale of the population and their homeland. The Dogon took inspiration from the Tellem (lit. “we found them”) sculptures recovered from caves on the escarpment, notably human figures with upraised arms in what is believed to be a prayer for rainfall. Most figures were not made to be seen publicly, and are commonly kept by the spiritual leader (hogon) away from the public eye, in family houses or sanctuaries.

It is not an understatement to claim that the Dogon are obsessed with their ancestors, both historical and mythical. This figure probably relates to a real or fictional ancestor, such as the semi-human nommo that feature at the very genesis of the Dogon people. This is a remarkable and imposing piece of African art.