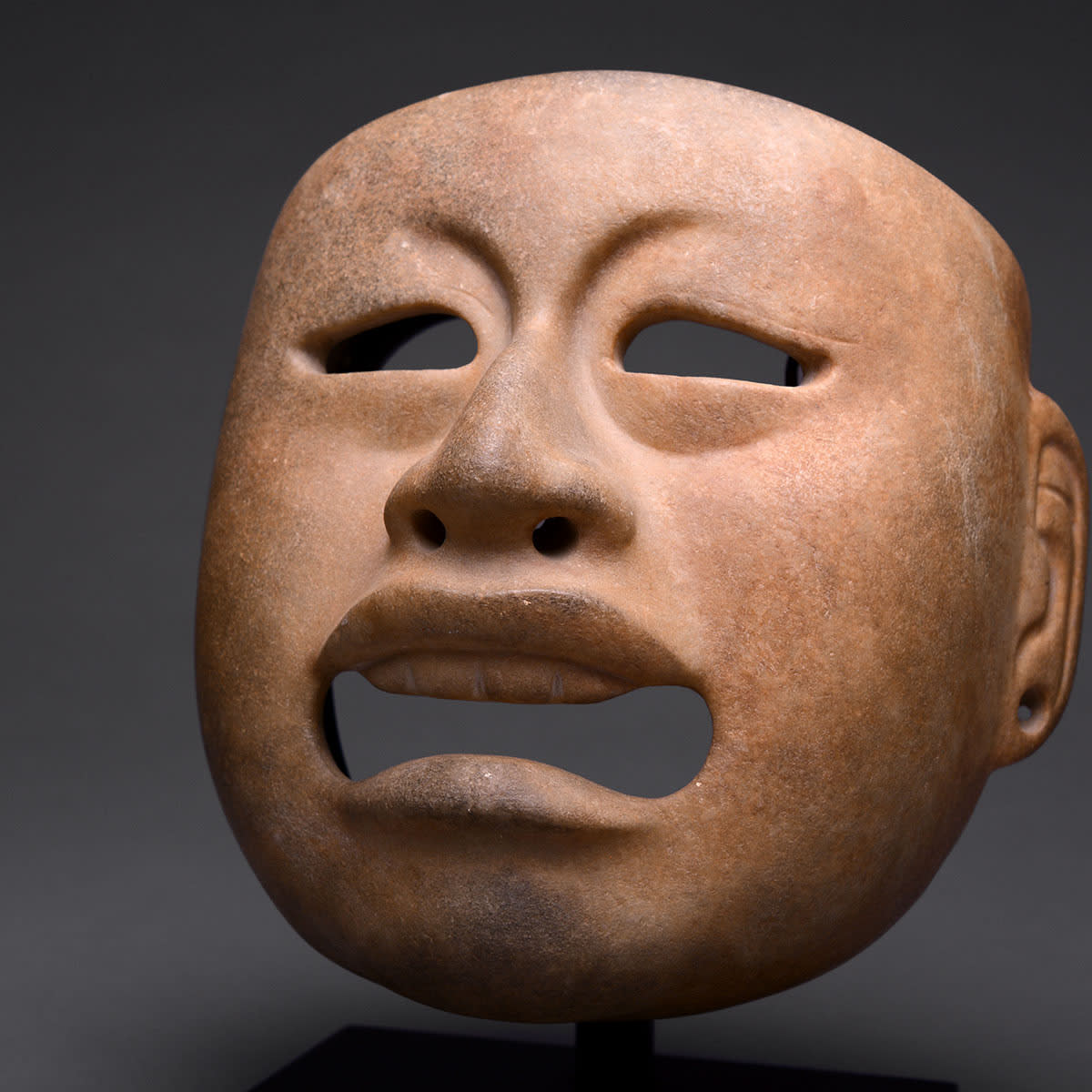

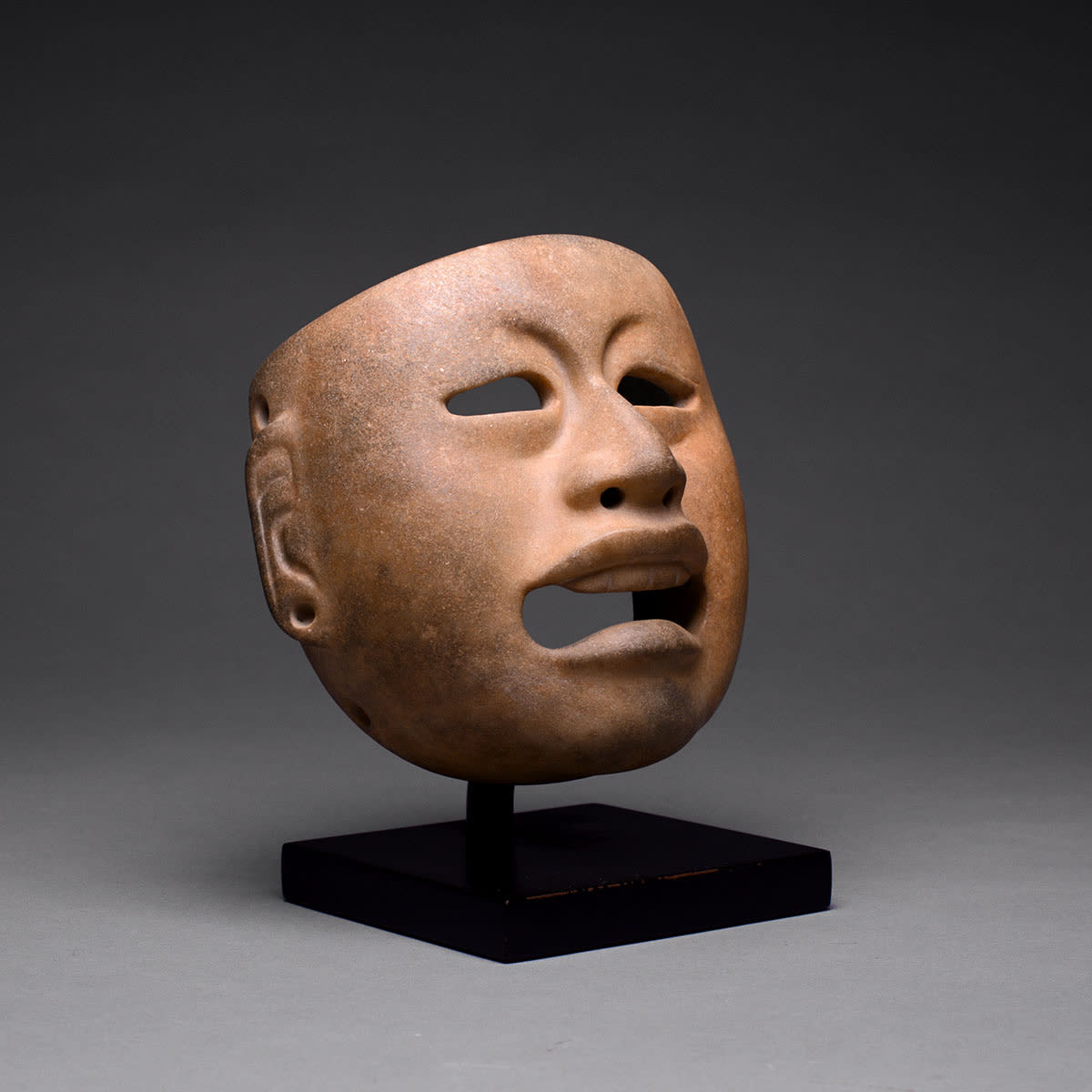

Olmec Jadite Mask, 1200 BCE - 500 BCE

Jadite

17.8 x 16.5 cm

7 x 6 1/2 in

7 x 6 1/2 in

CK.0788

Further images

The Olmecs are generally considered to be the ultimate ancestor of all subsequent Mesoamerican civilisations. Thriving between about 1200 and 400 BC, their base was the tropical lowlands of south...

The Olmecs are generally considered to be the ultimate ancestor of all subsequent Mesoamerican civilisations. Thriving between about 1200 and 400 BC, their base was the tropical lowlands of south central Mexico, an area characterized by swamps punctuated by low hill ridges and volcanoes. Here the Olmecs practiced advanced farming techniques and constructed many permanent settlements. Their influence, both cultural and political, extended far beyond their boundaries; the exotic nature of Olmec designs became synonymous with elite status in other (predominantly highland) groups, with evidence for exchange of artefacts in both directions. Other than their art (see below), they are credited with the foundations of writing systems (the loosely defined Epi-Olmec period, c. 500 BC), the first use of the zero – so instrumental in the Maya long count vigesimal calendrical system – and they also appear to have been the originators of the famous Mesoamerican ballgame so prevalent among later cultures in the region.

The art form for which the Olmecs are best known, the monumental stone heads weighing up to forty tons, are generally believed to depict kingly leaders or possibly ancestors. Other symbols abound in their stylistic repertoire, including several presumably religious symbols such as the feathered serpent and the rain spirit, which persisted in subsequent and related cultures until the middle ages. Comparatively little is known of their magico-religious world, although the clues that we have are tantalising. Technically, these include all non- secular items, of which there is a fascinating array. The best- known forms are jade and ceramic figures and celts that depict men, animals and fantastical beasts with both anthropomorphic and zoomorphic characteristics. Their size and general appearance suggests that they were domestically- or institutionally-based totems or divinities. The quality of production is astonishing, particularly if one considers the technology available, the early date of the pieces, and the dearth of earlier works upon which the Olmec sculptors could draw. Some pieces are highly stylised, while others demonstrate striking naturalism with deliberate expressionist interpretation of some facial features (notably up- turned mouths and slit eyes) that can be clearly seen in the current figure.

In the Olmec culture the mask was considered an icon of transformation. It makes visible the charismatic and shamanic power of the wearer; who was either a ruler or shaman. Often the mask has an expression of an otherworldly nature, as if submerged in an ecstatic trance. A mask will never change, it is unaffected by emotion or time, and will forever express the virtues the sculptor endowed upon it. This quality of the eternal appealed to Olmec rulers. The sheer power of this stone mask is monumental in scope. There is a sense it is a product of nature, elemental and beyond comprehension. Yet, a very skilled sculptor was needed to carve the intricate designs. This is not difficult to imagine given its almost primordial character, which seems to come from another dimension. In many respects the Olmec themselves seem not to have been of this world; and objects such as this extraordinary mask appear as living proof. Today, masks are worn mostly for the fun of Halloween parties or the profit of robbing banks. In either case their purpose is simply to conceal the identity of the wearer. The peoples of ancient cultures, however, believed that masks were magical and that by donning one the wearer actually became the god, demon or animal it represented and was, therefore, endowed with all its powers of good or evil. Masks of every conceivable non- perishable material and varying sizes have been found all over Mexico. The earliest we know of were made of clay but it is probable that others made of gourds or even paper have not survived. Jade, as the symbol of life and the most precious substance known, was often used for the most prestigious kings and powerful gods. Masks were frequently laid over the faces or on the chests of the dead. Though their actual purpose is obscure, at least one, that found in the tomb of a Pakal, ruler of Palenque, seems to have been a true portrait of the deceased.

The art form for which the Olmecs are best known, the monumental stone heads weighing up to forty tons, are generally believed to depict kingly leaders or possibly ancestors. Other symbols abound in their stylistic repertoire, including several presumably religious symbols such as the feathered serpent and the rain spirit, which persisted in subsequent and related cultures until the middle ages. Comparatively little is known of their magico-religious world, although the clues that we have are tantalising. Technically, these include all non- secular items, of which there is a fascinating array. The best- known forms are jade and ceramic figures and celts that depict men, animals and fantastical beasts with both anthropomorphic and zoomorphic characteristics. Their size and general appearance suggests that they were domestically- or institutionally-based totems or divinities. The quality of production is astonishing, particularly if one considers the technology available, the early date of the pieces, and the dearth of earlier works upon which the Olmec sculptors could draw. Some pieces are highly stylised, while others demonstrate striking naturalism with deliberate expressionist interpretation of some facial features (notably up- turned mouths and slit eyes) that can be clearly seen in the current figure.

In the Olmec culture the mask was considered an icon of transformation. It makes visible the charismatic and shamanic power of the wearer; who was either a ruler or shaman. Often the mask has an expression of an otherworldly nature, as if submerged in an ecstatic trance. A mask will never change, it is unaffected by emotion or time, and will forever express the virtues the sculptor endowed upon it. This quality of the eternal appealed to Olmec rulers. The sheer power of this stone mask is monumental in scope. There is a sense it is a product of nature, elemental and beyond comprehension. Yet, a very skilled sculptor was needed to carve the intricate designs. This is not difficult to imagine given its almost primordial character, which seems to come from another dimension. In many respects the Olmec themselves seem not to have been of this world; and objects such as this extraordinary mask appear as living proof. Today, masks are worn mostly for the fun of Halloween parties or the profit of robbing banks. In either case their purpose is simply to conceal the identity of the wearer. The peoples of ancient cultures, however, believed that masks were magical and that by donning one the wearer actually became the god, demon or animal it represented and was, therefore, endowed with all its powers of good or evil. Masks of every conceivable non- perishable material and varying sizes have been found all over Mexico. The earliest we know of were made of clay but it is probable that others made of gourds or even paper have not survived. Jade, as the symbol of life and the most precious substance known, was often used for the most prestigious kings and powerful gods. Masks were frequently laid over the faces or on the chests of the dead. Though their actual purpose is obscure, at least one, that found in the tomb of a Pakal, ruler of Palenque, seems to have been a true portrait of the deceased.