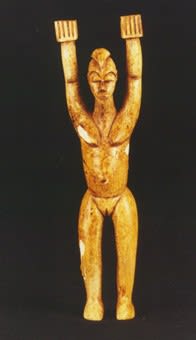

Lobi Ivory Bateba Sculpture of a Standing Woman, 20th Century CE

Ivory

10

PF.4550 (LSO)

This striking ivory sculpture is a bateba figure from the Lobi group of Burkina Faso. It is remarkable in terms of its rarity – ivory figures are far from common...

This striking ivory sculpture is a bateba figure from the Lobi group of Burkina Faso. It is remarkable in terms of its rarity – ivory figures are far from common – as well as its preservation and the unusual pose in which it has been sculpted, as position is extremely important when analysing these pieces (see below). The piece constitutes a naked standing woman with a columnar body and attenuated limbs, standing with her arms in the air. Her construction is compartmental, with the legs sectioned from the trunk by a triangular discontinuity at the hips. Her arms are likewise sectorial, each delineated with the breast from its respective side by strategic incised lines. The effect is deconstructed and geometric. The upper/forearms are separated, but the legs are continuous without a break for the knees. The hands are schematic with block fingers. The neck is elongated, with a tall head bearing a vertical geometric coiffure. The brows are arched, with closed eyes, a retrousse nose and a nugatory mouth. The ivory has become darkened through use and the application of libations. Further details as to its original use are supplied below.

The Lobi – whose name literally means “children [lou] of the forest [bi]” in Lobiri – are a large group living across Ghana, Togo and Burkina Faso. The term “Lobi” covers various subclans (including the Lobi, Birifor, Dagara, Dorossy, Dyan, Gan and Teguessy) which can be differentiated, but which are usually identified as a homogenous unit from outside. They share common traits in terms of architecture and village structure, and – for our purposes – similar social/religious beliefs and thus artistic production.

The Lobi were founded sometime in the 18th century, when they loved to their current territory. The country is intimately tied up in their beliefs. For example, the main river along which they settled – the Mounhoun – is believed to symbolise the division between this world and there hereafter, and must be crossed upon death; for this reason many Lobi initiation rites take place on its banks, and the animals which frequent it and its surrounds are considered sacred. They are an exceptionally martial group, and have a long history of struggles and sanguineous battles with long-serving enemies including the Guiriko and Kenedougou empires. The French, unsurprisingly, had problems with colonial administration in the area, and embarked upon a bloodbath of oppression in order to bring them under control. This powerful resistance also extended to Christianity, which the Lobi have eschewed for decades. Christian missionaries working in southern Burkina Faso reported that an elderly man in a Lobi village renounced the spirits in favor of Christianity by discarding his fetishes in a nearby lake. As he turned his back on the traditions, the fetishes leapt out of the lake onto his back again to reclaim him. Possibly for this reason, the artefacts associated with traditional belief systems are comparatively common, and display a healthy range of diversity that is often absent in older pieces from areas where the formidable power of forced Christianity was brought to bear upon the native populations.

Lobi artistic production is intimately tied up with their beliefs. They are governed by a set of social conduct rules that are known as “zosar” Ancestors and fetishes of various sorts are commonplace, both domestically and on a wider social scale. They appeal to “thila” (or thil) spirits, who act as intermediaries between this world and high-power deities such as the creator god (Thagba). Access to the thila is controlled by the thildar, or diviner. The Lobi commission – with the help of the village sorcerer – figures known as “bateba”. These serve either an apotropaic function (Bateba Duntundora) or act as personifications of thila whose personal qualities are especially desirable. In the latter category, the specific sentiments are expressed by body position. The figures with one arm upstretched, for example, indicate a dangerous thil spirit, while erotic thil duos are designed to guarantee fertility to the females in whatever house it is displayed. It is likely that many of the variants reflect personal characteristics of thila, with corpulent, jolly or dejected individuals all known from older collections. However, there is a distinctive subset of bateba known as “bateba yadawora” – literally “unhappy bateba” – whose expressions and stances are believed to reflect sadness and mournfulness, and thus take any such sentiments away from their owners. Bateba are usually kept on domestic shrines inside or even on top of homes, and are revered alongside a number of other objects including iron statues and ceramic vessels that are often appeased and appealed to by the sacrifice of food, drink and miscellaneous substances, and many bateba still retain some encrusted offerings.

The current piece is evidence that, like most human groups, the Lobi were prey to conspicuous consumption. It is a very rare piece as ivory was only used in the wealthiest of homes. This is a truly exceptional piece of Lobi art.

The Lobi – whose name literally means “children [lou] of the forest [bi]” in Lobiri – are a large group living across Ghana, Togo and Burkina Faso. The term “Lobi” covers various subclans (including the Lobi, Birifor, Dagara, Dorossy, Dyan, Gan and Teguessy) which can be differentiated, but which are usually identified as a homogenous unit from outside. They share common traits in terms of architecture and village structure, and – for our purposes – similar social/religious beliefs and thus artistic production.

The Lobi were founded sometime in the 18th century, when they loved to their current territory. The country is intimately tied up in their beliefs. For example, the main river along which they settled – the Mounhoun – is believed to symbolise the division between this world and there hereafter, and must be crossed upon death; for this reason many Lobi initiation rites take place on its banks, and the animals which frequent it and its surrounds are considered sacred. They are an exceptionally martial group, and have a long history of struggles and sanguineous battles with long-serving enemies including the Guiriko and Kenedougou empires. The French, unsurprisingly, had problems with colonial administration in the area, and embarked upon a bloodbath of oppression in order to bring them under control. This powerful resistance also extended to Christianity, which the Lobi have eschewed for decades. Christian missionaries working in southern Burkina Faso reported that an elderly man in a Lobi village renounced the spirits in favor of Christianity by discarding his fetishes in a nearby lake. As he turned his back on the traditions, the fetishes leapt out of the lake onto his back again to reclaim him. Possibly for this reason, the artefacts associated with traditional belief systems are comparatively common, and display a healthy range of diversity that is often absent in older pieces from areas where the formidable power of forced Christianity was brought to bear upon the native populations.

Lobi artistic production is intimately tied up with their beliefs. They are governed by a set of social conduct rules that are known as “zosar” Ancestors and fetishes of various sorts are commonplace, both domestically and on a wider social scale. They appeal to “thila” (or thil) spirits, who act as intermediaries between this world and high-power deities such as the creator god (Thagba). Access to the thila is controlled by the thildar, or diviner. The Lobi commission – with the help of the village sorcerer – figures known as “bateba”. These serve either an apotropaic function (Bateba Duntundora) or act as personifications of thila whose personal qualities are especially desirable. In the latter category, the specific sentiments are expressed by body position. The figures with one arm upstretched, for example, indicate a dangerous thil spirit, while erotic thil duos are designed to guarantee fertility to the females in whatever house it is displayed. It is likely that many of the variants reflect personal characteristics of thila, with corpulent, jolly or dejected individuals all known from older collections. However, there is a distinctive subset of bateba known as “bateba yadawora” – literally “unhappy bateba” – whose expressions and stances are believed to reflect sadness and mournfulness, and thus take any such sentiments away from their owners. Bateba are usually kept on domestic shrines inside or even on top of homes, and are revered alongside a number of other objects including iron statues and ceramic vessels that are often appeased and appealed to by the sacrifice of food, drink and miscellaneous substances, and many bateba still retain some encrusted offerings.

The current piece is evidence that, like most human groups, the Lobi were prey to conspicuous consumption. It is a very rare piece as ivory was only used in the wealthiest of homes. This is a truly exceptional piece of Lobi art.