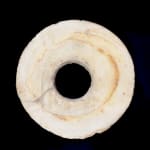

Kohl Jar, with Lid and Kohl Residue, 1635 BC - 1458 BC

Calcite, Galena

7.2 x 7.1 cm

2 7/8 x 2 3/4 in

2 7/8 x 2 3/4 in

CC.258

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 15

)

Famously, the Greek historian Herodotos considered Egypt as ‘the gift of the Nile’ (2.5.1). He was, in many respects, correct. The world’s greatest river was the backbone of Egyptian civilisation....

Famously, the Greek historian Herodotos considered Egypt as ‘the gift of the Nile’ (2.5.1). He was, in many respects, correct. The world’s greatest river was the backbone of Egyptian civilisation. The waters of the river cut a great trail of blue and green through the vast and unyielding desert that hemmed it in on both sides, before fanning out into the fertile and marshy Nile Delta, where the river discharged into the Mediterranean Sea. The river was not only a rare source of freshwater in the otherwise barren desert, but also flooded annually, submerging a thin area on either bank, and depositing there thick organically-rich mud which was brought up from the highlands of Ethiopia and the jungles further south. When the waters receded, the Egyptians were left with some of the richest farmlands in the entire ancient world. The ideal Egyptian settlement was on the fringes of this fertile land, close enough to the river to give access to the life-supporting waters, yet far enough away not to impinge on the vital soils. Unfortunately, the fringes of the desert were not an ideal living environment. The desert winds whipped up sand and grit which impregnated the air, while the moisture of the river valley encouraged insects, many of which were vectors of disease. As a result, illnesses were commonplace, and ophthalmological complaints were common enough that numerous papyrus treatises were written listing their treatments. The most popular of these treatments was a preventative one: the wearing of kohl around the eyes. Kohl, a compound of lead or antimony sulphide, was ground into a thick black paint which was used as eyeliner by Egyptians of all classes. While it was believed that kohl would protect the eyes from harsh sunlight, grit and insects, the toxicity of both lead and antimony suggests that it may have caused more problems than it solved.

Both practically and spiritually important, kohl was a central part of the Egyptian daily life, and certainly no person of any status would be seen dead without it – literally. Accoutrements for the preparation, application and storage of kohl are therefore among the commonest finds from Egyptian tombs, and among the most important categories of finds from Egypt. Indeed, two of the earliest masterpieces of Egyptian art – the Two Dogs (AN1896-1908 E.3924) and Narmer (Egyptian Museum, Cairo CG 14716) Palettes – were surfaces on which kohl could be ground and mixed with water. As Egyptian history progressed, the trend moved towards keeping pre-prepared kohl in specially-designed cosmetic vases, with snug-fitting lids to prevent the paste from drying out. Kohl jars came in a bewildering variety of forms, from the mundane to the exceptional. Remarkable figural vases, for example, in the form of hedgehogs (British Museum EA58323) or the deity Bes (Akademisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn 1897), were at the higher end of the market. But even everyday kohl vessels were beautiful objects, produced in striking blue faience (e.g. British Museum EA24391) or, more usually, carved from stone. The most esteemed stone for kohl jars was alabaster. In Egypt, alabaster is an archaeological rather than a geological term, referring to a milky-white to honey yellow dense rock with bands of orange, brown, black, grey and white throughout. This rock – properly called banded travertine – was considered sacred by the Egyptians for its ability to transmit light. When held up against a light-source, polished travertine seems to glow, and was therefore related in Egyptian thought to the journey of the sun-god Ra through the underworld. As a result, it was especially used for sepulchral objects.

This little kohl pot follows a design which was barely changed for centuries. Originating in the Middle Kingdom, around the Eleventh Dynasty (2150 BC – 1991 BC), these kinds of kohl pots with a squat, round body, a slightly everted foot, a dramatic shoulder, narrow neck, and flared outfaced rim became the classical form repeated until the end of Egyptian history. Minor variations allow us to date individual examples; the fact that the body is less squat and wide than other examples, and the thickness and V-shaped profile of the rim, place this example in the New Kingdom, around the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550 BC – 1292 BC), corresponding to Petrie’s number 740 (Petrie, W. M, F, (1937) The Funeral Furniture of Egypt, with Stone and Metal Vases, London.). Like all kohl vessels of this type, the entire centre is not hollowed out, but rather a small well is drilled into the stone. The thickness of the walls may have served to insulate the kohl from the variable temperatures outside. The jar is topped with a snug-fitting disc-shaped lid, which is now broken, which would also have prevented the paste from drying out. Perhaps most excitingly, this particular example still has the residue of the kohl inside the well, which is stained a dark inky grey from use. This piece was almost certainly intended for a tomb, and this may be one reason why the kohl residue has survived. As a necessity in life, kohl was considered essential for the ka, or spirit, which would inhabit the afterlife. The presence of kohl in the tomb reflected the family’s desire to ensure that the deceased was well-provisioned in the Netherworld.

References: example kohl jars of this type and period can be found in London (British Museum EA63271), Oxford (Ashmolean Museum AN1896-1908.E.2333, AN1890.807), Liverpool (World Museum LL5146). New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 35.3.22, 16.10.372, 16.10.238, 16.10.239), Boston (Museum of Fine Arts 08.1, 11.2423, 11.2424, 11.2435).

Both practically and spiritually important, kohl was a central part of the Egyptian daily life, and certainly no person of any status would be seen dead without it – literally. Accoutrements for the preparation, application and storage of kohl are therefore among the commonest finds from Egyptian tombs, and among the most important categories of finds from Egypt. Indeed, two of the earliest masterpieces of Egyptian art – the Two Dogs (AN1896-1908 E.3924) and Narmer (Egyptian Museum, Cairo CG 14716) Palettes – were surfaces on which kohl could be ground and mixed with water. As Egyptian history progressed, the trend moved towards keeping pre-prepared kohl in specially-designed cosmetic vases, with snug-fitting lids to prevent the paste from drying out. Kohl jars came in a bewildering variety of forms, from the mundane to the exceptional. Remarkable figural vases, for example, in the form of hedgehogs (British Museum EA58323) or the deity Bes (Akademisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn 1897), were at the higher end of the market. But even everyday kohl vessels were beautiful objects, produced in striking blue faience (e.g. British Museum EA24391) or, more usually, carved from stone. The most esteemed stone for kohl jars was alabaster. In Egypt, alabaster is an archaeological rather than a geological term, referring to a milky-white to honey yellow dense rock with bands of orange, brown, black, grey and white throughout. This rock – properly called banded travertine – was considered sacred by the Egyptians for its ability to transmit light. When held up against a light-source, polished travertine seems to glow, and was therefore related in Egyptian thought to the journey of the sun-god Ra through the underworld. As a result, it was especially used for sepulchral objects.

This little kohl pot follows a design which was barely changed for centuries. Originating in the Middle Kingdom, around the Eleventh Dynasty (2150 BC – 1991 BC), these kinds of kohl pots with a squat, round body, a slightly everted foot, a dramatic shoulder, narrow neck, and flared outfaced rim became the classical form repeated until the end of Egyptian history. Minor variations allow us to date individual examples; the fact that the body is less squat and wide than other examples, and the thickness and V-shaped profile of the rim, place this example in the New Kingdom, around the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550 BC – 1292 BC), corresponding to Petrie’s number 740 (Petrie, W. M, F, (1937) The Funeral Furniture of Egypt, with Stone and Metal Vases, London.). Like all kohl vessels of this type, the entire centre is not hollowed out, but rather a small well is drilled into the stone. The thickness of the walls may have served to insulate the kohl from the variable temperatures outside. The jar is topped with a snug-fitting disc-shaped lid, which is now broken, which would also have prevented the paste from drying out. Perhaps most excitingly, this particular example still has the residue of the kohl inside the well, which is stained a dark inky grey from use. This piece was almost certainly intended for a tomb, and this may be one reason why the kohl residue has survived. As a necessity in life, kohl was considered essential for the ka, or spirit, which would inhabit the afterlife. The presence of kohl in the tomb reflected the family’s desire to ensure that the deceased was well-provisioned in the Netherworld.

References: example kohl jars of this type and period can be found in London (British Museum EA63271), Oxford (Ashmolean Museum AN1896-1908.E.2333, AN1890.807), Liverpool (World Museum LL5146). New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 35.3.22, 16.10.372, 16.10.238, 16.10.239), Boston (Museum of Fine Arts 08.1, 11.2423, 11.2424, 11.2435).