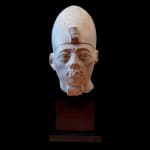

Portrait of a Pharaoh, probably Ahmose I, 1550 BC - 1525 BC

Granite

24.8 x 11.6 x 19.6 cm

9 3/4 x 4 5/8 x 7 3/4 in

9 3/4 x 4 5/8 x 7 3/4 in

CC.359

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

There were around 170 Pharaohs of Egypt across the nearly 3,000-year span before the Roman conquest. In the modern world, the names of some of these Pharaohs are as familiar...

There were around 170 Pharaohs of Egypt across the nearly 3,000-year span before the Roman conquest. In the modern world, the names of some of these Pharaohs are as familiar as our own contemporary world leaders: Ramses II, warrior-king and postulated Pharaoh of the Exodus; Tutankhamun, the boy-king buried with more gold and wonders than had ever been imagined before; Akhenaten, the religious revolutionary; Hatshepsut, the woman who ruled as a man; or Cleopatra, femme fatale and tragic heroine. They are the subjects of operas, Shakespeare, film, and novels, objects of public fascination and scholarly interest. But for the Egyptians of ancient times, looking back on their own history, there were only three Pharaohs who truly mattered above all others. They were not rulers of great wealth or power; they did not expand the Egyptian Empire to its greatest extent. Rather, they were unifiers, the individuals who founded and re-founded the Black Land (Kemet) as a single Nilotic Kingdom, fusing and reforging the once-opposed Two Lands of the Nile Delta and the Valley into a single country. The first of these Pharaohs was known variously as Narmer or Menes, a semi-legendary figure from the mid Fourth Millennium BC, who, as the Pharaoh of Upper Egypt, warred against and eventually overcame the Kings of Lower Egypt, and was the first to unify the land of the Nile from the Mediterranean Sea down to the First Cataract of the Nile. The second was Mentuhotep II, a ruler of the city of Thebes who emerged during a period of disunity called the First Intermediate Period. He brought Egypt back together after the turbulence, founding the period archaeologists know as the Middle Kingdom (2040 BC – 1782 BC).

The third, and in the view of many Egyptians, the most important, was Ahmose I. Like Mentuhotep II, Ahmose was born into a period of tumult, the Second Intermediate Period. During this collapse of Egyptian civilisation, foreign invaders known as the Hyksos, whose name derives from the Egyptian heqau khasut (‘rulers of foreign lands’), arrived from Western Asia, conquering the north of the country. Native Egyptians retained a foothold in the south, from where various ruling families attempted to regain control over the whole country. Eventually the Hyksos took control of Thebes, the largest city in Egypt and the centre of gravity in the south. It was in this chaotic setting that the Seventeenth Dynasty, a family of Theban nobles, emerged. They wrested back control of Thebes and began an offensive against the Hyksos. Pharaohs such as Seqenenre Tao and Kamose carved out a minor military advantage over the Hyksos. It was Kamose’s brother, Ahmose, who completed the job, and re-unified Egypt for a third and, sadly, final time. The state he founded, known as the Egyptian New Kingdom, endured for around a thousand years, and the Dynasty of his successors, the Eighteenth Dynasty, was perhaps Egypt’s most spectacular. Of the famed Pharaohs mentioned above, Tutankhamun, Hatshepsut, and Akhenaten were direct descendants of Ahmose, as were remarkable rulers like Amenhotep III and Thutmose III.

Little is known about Ahmose I’s actual reign as Pharaoh of a unified country. He was known to have campaigned militarily in both Syria and Nubia, in an attempt to expand Egypt’s borders and secure it from the persistent threats which had characterised much of the preceding centuries. His success was limited, and much of the work had to be redone by great campaigning Pharaohs like Thutmose III, Seti I, and Ramses II. He was known to be a great investor in the country’s temples, expanding many of the most important religious foundations in his home-city of Thebes, but also in Egypt’s historical capital, Memphis. He sponsored a number of artisans, especially in the field of glassmaking, And Ahmose I was the last Egyptian Pharaoh to occupy one of those grandest of tombs, a pyramid. His pyramid is now a sorry sight, having been stripped of its outer casing of gleaming white limestone, and allowed to crumble. But some archaeologists believe that his mummy was rescued, and a mummy which is claimed to be his is now at the Luxor Museum, on permanent loan from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (CG 61057).

This remarkable portrait is identified as Ahmose I on account of two notable details. The first is the close physical resemblance of this figure to the known portrait of Ahmose I at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2006.270). This Pharaoh is depicted, like the confirmed Ahmose, as wearing the hedjet, a bottle-shaped white crown fronted with a single uraeus (rearing cobra) associated with Upper Egypt, which reminds the viewer of his origins in the south of the country. His eyes are wide and taper to elegant points, outlined by the kohl worn by Egyptians of all classes to keep insects and harmful dust from their eyes. Note especially that the tear ducts are depicted as lower than the actual eye, and deeply pointed, with the axis of the eye angled slightly downwards such that the Pharaoh appears to be looking down on the viewer. The eyebrows are sympathetically arched, and the slight archaic smile is enhanced by a prominent philtrum. The naso-labial folds are clearly, if delicately, incised. The ears, though damaged, appear to have been large and to stick outwards, in recognition of the King’s readiness to hear the prayers and supplications of his subjects. Earlier Pharaohs, especially Senusret III, emphasised this feature, and it is possible that Ahmose I included this same feature on his own statuary in order to demonstrate continuity with the Middle Kingdom. These features also appear in one of the few other stone representations of Ahmose, his shabti, currently at the British Museum in London (EA32191). With this latter portrait, we also see commonality in the flatness of the chin, which is almost squared-off above the fragmentary false beard, and the prominent zygomatic bone, which is flared close to the eye. This portrait is moderately less plump than the other two main surviving portraits of Ahmose, but this may represent an attempt to project a more mature, contemplative image of this young and restless Pharaoh. Such indications of age are rare but not unparalleled in Egyptian sculpture of monarchs; Senusret III, who we have already noted as potential inspiration for this portrait’s large ears, was also often presented in more mature guise. Ahmose I, who had a vested interest in presenting continuity with the Pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom, may have used statues of Senusret III as a model for his own image. In all, the craniofacial analysis of this portrait versus those in the Metropolitan and British Museums, is favourable for a positive identification as Ahmose I. These features prefigure the later development of what was called the Thutmosid Style, adopted during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty.

The other feature which enables identification of this Pharaoh is the column on the reverse. Designed to increase the stability of, especially standing, statues, back-pillars became an additional decorative surface on which Egyptian sculptors could add hieroglyphic captions expressing the identity of the subject. The back-pillar of this figure is sadly highly fragmentary, but a few hieroglyphs can be identified. The six legs of Gardner Sign L2, the bee, and the lower portion of sign M23, the sedge plant, along with two bread loaves representing the letter ‘t’, introduce this as one of the most important royal titles, the throne name or praenomen (nswt bty), literally ‘he of the sedge and the bee’, referring to the pseudo-heraldic symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt respectively. Clearer are the following signs, nb twy, ‘lord of the two lands’, followed by two small strokes which emphasise the duality expressed in both of these titles. Then comes the top of a cartouche, the protective rope loop which guards the name of the Pharaoh. Within this cartouche would have been the throne name of the King; alas, the only sign which remains is a sun-disk, Gardiner Sign N5. This represents both the syllable ‘ra’ and the name of the sun-god Ra. Through a process known as honorific transposition, this sign would always come first in a name or word, since it bears this dual meaning as a god’s name. As such, it was the first syllable in Ahmose I’s throne name ‘Neb-pehty-Ra’, which literally translates as ‘the possessor of the might of Ra’. The word pehty (‘might’) is sometimes expressed in Egyptian as a plural, perhaps better translated as ‘mightinesses’ or ‘mighty deeds’, in which case the sign, a lion’s head, would be repeated, or else the feminine -t ending might be repeated. The feminine -t ending was expressed through the same sign – a loaf of bread – as appears under the sedge and bee in the introduction to his title. It is likely that this format would have been adopted here, to provide a kind of symmetry so beloved of Egyptian calligraphers.

Executed in smooth, finely crystalline, grey granite which emphasises both the sternness and sympathy of the Pharaoh’s expression, this is a very rare survival from Ahmose I’s twenty-five-year reign. While this is exceptionally similar to the example held by the Metropolitan Museum, the only other example outside of Egypt of Ahmose’s portrait in-the-round, it must be emphasised that the Barakat portrait is much more refined, more delicate, and more aesthetically harmonious. Whereas the Metropolitan’s example has wild, wide eyes, the Barakat portrait’s are sensitive and contemplative. We can almost see in the Pharaoh’s face the world-weariness of a campaigning soldier who, freeing Egypt in perhaps his late teens or early twenties, had lost much of the aggressive spirit which characterised his youth. The curve of the neck, and the slight flare of the shoulder, evidence that this was once a full-length statue, depicting the Pharaoh seated or, given he had a supportive back pillar, standing in a striding pose, left leg before his right, arms held down by his sides, hands held in fists, in a pose of power and dynamism. For such an important monarch, few images of Ahmose I exist. Only three representations of sculpture-in-the-round depicting Ahmose are known; the positive identification of this figure as Ahmose I would add a fourth.

Translation: He of the Sedge and the Bee, Lord of the Two Lands, [Neb-pehty-]Ra…

References: a comparable sculpture-in-the-round of Ahmose I is currently held in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2006.270). The face of the Barakat portrait is remarkably similar to that of the shabti of Ahmose I, currently in London (British Museum EA32191).

The third, and in the view of many Egyptians, the most important, was Ahmose I. Like Mentuhotep II, Ahmose was born into a period of tumult, the Second Intermediate Period. During this collapse of Egyptian civilisation, foreign invaders known as the Hyksos, whose name derives from the Egyptian heqau khasut (‘rulers of foreign lands’), arrived from Western Asia, conquering the north of the country. Native Egyptians retained a foothold in the south, from where various ruling families attempted to regain control over the whole country. Eventually the Hyksos took control of Thebes, the largest city in Egypt and the centre of gravity in the south. It was in this chaotic setting that the Seventeenth Dynasty, a family of Theban nobles, emerged. They wrested back control of Thebes and began an offensive against the Hyksos. Pharaohs such as Seqenenre Tao and Kamose carved out a minor military advantage over the Hyksos. It was Kamose’s brother, Ahmose, who completed the job, and re-unified Egypt for a third and, sadly, final time. The state he founded, known as the Egyptian New Kingdom, endured for around a thousand years, and the Dynasty of his successors, the Eighteenth Dynasty, was perhaps Egypt’s most spectacular. Of the famed Pharaohs mentioned above, Tutankhamun, Hatshepsut, and Akhenaten were direct descendants of Ahmose, as were remarkable rulers like Amenhotep III and Thutmose III.

Little is known about Ahmose I’s actual reign as Pharaoh of a unified country. He was known to have campaigned militarily in both Syria and Nubia, in an attempt to expand Egypt’s borders and secure it from the persistent threats which had characterised much of the preceding centuries. His success was limited, and much of the work had to be redone by great campaigning Pharaohs like Thutmose III, Seti I, and Ramses II. He was known to be a great investor in the country’s temples, expanding many of the most important religious foundations in his home-city of Thebes, but also in Egypt’s historical capital, Memphis. He sponsored a number of artisans, especially in the field of glassmaking, And Ahmose I was the last Egyptian Pharaoh to occupy one of those grandest of tombs, a pyramid. His pyramid is now a sorry sight, having been stripped of its outer casing of gleaming white limestone, and allowed to crumble. But some archaeologists believe that his mummy was rescued, and a mummy which is claimed to be his is now at the Luxor Museum, on permanent loan from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (CG 61057).

This remarkable portrait is identified as Ahmose I on account of two notable details. The first is the close physical resemblance of this figure to the known portrait of Ahmose I at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2006.270). This Pharaoh is depicted, like the confirmed Ahmose, as wearing the hedjet, a bottle-shaped white crown fronted with a single uraeus (rearing cobra) associated with Upper Egypt, which reminds the viewer of his origins in the south of the country. His eyes are wide and taper to elegant points, outlined by the kohl worn by Egyptians of all classes to keep insects and harmful dust from their eyes. Note especially that the tear ducts are depicted as lower than the actual eye, and deeply pointed, with the axis of the eye angled slightly downwards such that the Pharaoh appears to be looking down on the viewer. The eyebrows are sympathetically arched, and the slight archaic smile is enhanced by a prominent philtrum. The naso-labial folds are clearly, if delicately, incised. The ears, though damaged, appear to have been large and to stick outwards, in recognition of the King’s readiness to hear the prayers and supplications of his subjects. Earlier Pharaohs, especially Senusret III, emphasised this feature, and it is possible that Ahmose I included this same feature on his own statuary in order to demonstrate continuity with the Middle Kingdom. These features also appear in one of the few other stone representations of Ahmose, his shabti, currently at the British Museum in London (EA32191). With this latter portrait, we also see commonality in the flatness of the chin, which is almost squared-off above the fragmentary false beard, and the prominent zygomatic bone, which is flared close to the eye. This portrait is moderately less plump than the other two main surviving portraits of Ahmose, but this may represent an attempt to project a more mature, contemplative image of this young and restless Pharaoh. Such indications of age are rare but not unparalleled in Egyptian sculpture of monarchs; Senusret III, who we have already noted as potential inspiration for this portrait’s large ears, was also often presented in more mature guise. Ahmose I, who had a vested interest in presenting continuity with the Pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom, may have used statues of Senusret III as a model for his own image. In all, the craniofacial analysis of this portrait versus those in the Metropolitan and British Museums, is favourable for a positive identification as Ahmose I. These features prefigure the later development of what was called the Thutmosid Style, adopted during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty.

The other feature which enables identification of this Pharaoh is the column on the reverse. Designed to increase the stability of, especially standing, statues, back-pillars became an additional decorative surface on which Egyptian sculptors could add hieroglyphic captions expressing the identity of the subject. The back-pillar of this figure is sadly highly fragmentary, but a few hieroglyphs can be identified. The six legs of Gardner Sign L2, the bee, and the lower portion of sign M23, the sedge plant, along with two bread loaves representing the letter ‘t’, introduce this as one of the most important royal titles, the throne name or praenomen (nswt bty), literally ‘he of the sedge and the bee’, referring to the pseudo-heraldic symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt respectively. Clearer are the following signs, nb twy, ‘lord of the two lands’, followed by two small strokes which emphasise the duality expressed in both of these titles. Then comes the top of a cartouche, the protective rope loop which guards the name of the Pharaoh. Within this cartouche would have been the throne name of the King; alas, the only sign which remains is a sun-disk, Gardiner Sign N5. This represents both the syllable ‘ra’ and the name of the sun-god Ra. Through a process known as honorific transposition, this sign would always come first in a name or word, since it bears this dual meaning as a god’s name. As such, it was the first syllable in Ahmose I’s throne name ‘Neb-pehty-Ra’, which literally translates as ‘the possessor of the might of Ra’. The word pehty (‘might’) is sometimes expressed in Egyptian as a plural, perhaps better translated as ‘mightinesses’ or ‘mighty deeds’, in which case the sign, a lion’s head, would be repeated, or else the feminine -t ending might be repeated. The feminine -t ending was expressed through the same sign – a loaf of bread – as appears under the sedge and bee in the introduction to his title. It is likely that this format would have been adopted here, to provide a kind of symmetry so beloved of Egyptian calligraphers.

Executed in smooth, finely crystalline, grey granite which emphasises both the sternness and sympathy of the Pharaoh’s expression, this is a very rare survival from Ahmose I’s twenty-five-year reign. While this is exceptionally similar to the example held by the Metropolitan Museum, the only other example outside of Egypt of Ahmose’s portrait in-the-round, it must be emphasised that the Barakat portrait is much more refined, more delicate, and more aesthetically harmonious. Whereas the Metropolitan’s example has wild, wide eyes, the Barakat portrait’s are sensitive and contemplative. We can almost see in the Pharaoh’s face the world-weariness of a campaigning soldier who, freeing Egypt in perhaps his late teens or early twenties, had lost much of the aggressive spirit which characterised his youth. The curve of the neck, and the slight flare of the shoulder, evidence that this was once a full-length statue, depicting the Pharaoh seated or, given he had a supportive back pillar, standing in a striding pose, left leg before his right, arms held down by his sides, hands held in fists, in a pose of power and dynamism. For such an important monarch, few images of Ahmose I exist. Only three representations of sculpture-in-the-round depicting Ahmose are known; the positive identification of this figure as Ahmose I would add a fourth.

Translation: He of the Sedge and the Bee, Lord of the Two Lands, [Neb-pehty-]Ra…

References: a comparable sculpture-in-the-round of Ahmose I is currently held in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2006.270). The face of the Barakat portrait is remarkably similar to that of the shabti of Ahmose I, currently in London (British Museum EA32191).