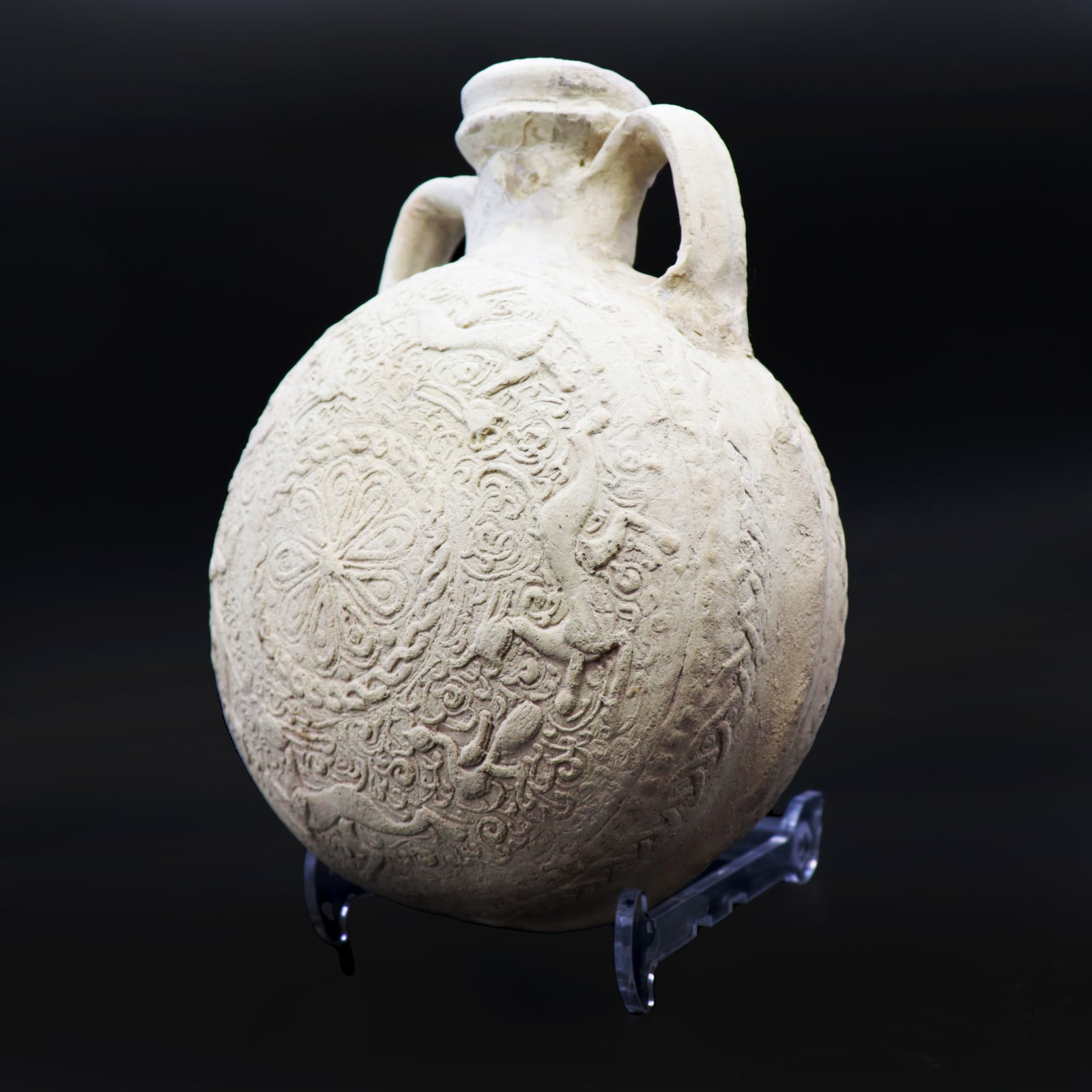

Umayyad or Abbasid Unglazed Pilgrim Flask, Seventh to Ninth Centuries AD

Ceramic

26 x 20 x 15.5 cm

10 1/4 x 7 7/8 x 6 1/8 in

10 1/4 x 7 7/8 x 6 1/8 in

CC.80

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

Following the death of the prophet Muhammad in AD 632, the future of Islam lay in the hands of four successive Caliphs, who sought to build on Muhammad’s legacy and...

Following the death of the prophet Muhammad in AD 632, the future of Islam lay in the hands of four successive Caliphs, who sought to build on Muhammad’s legacy and expand the frontiers of Islam. The final of these Caliphs, Muhammad’s cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, deposed various regional governors, whom he considered corrupt. This included Mu’awiya, the brother of a previous Caliph; Mu’awiya would not tolerate such an indignity, and began a brutal and bloody civil war, known as the First Fitna. The conflict ended with the assassination of Ali, as he prayed in the Mosque of Kufa, in AD 661. Mu’awiya became Caliph, and founded the Umayyad Dynasty. No longer would the Caliph be chosen by his predecessor, or by a council of leading Muslims. Instead, the Caliphate became a hereditary monarchy, with Mu’awiya at the centre. For a hundred years, Mu’awiya and his successors dominated the Muslim world. But this was not to last; they were overthrown by the Abbasid Dynasty, descended from Muhammad’s uncle Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, and supported by the followers of Ali, who never accepted his assassination or the new Umayyad rule.

The Umayyads and the subsequent Abbasids laid the foundation for Islamic art. At first, the main influences were the Late Antique naturalistic tradition, and the more formal modes of Byzantine and Sassanid art. But gradually, the Islamic world began to formulate its own artistic forms, focussed especially on animal, vegetal and figural motifs. This conflation of the old and new can be seen in this large, unglazed, pilgrim flask. The form is very old indeed: pilgrim flasks are known from the early part of the Bronze Age in the Levant, and continued to be produced throughout the Roman and Byzantine Eras. Their name derives from this later period, when the form was used by Christian (and later Muslim) pilgrims to collect and store water which had been poured over sacred sites and objects. It consists of a large spherical body, moulded in two halves and joined with a hand-pressed seam in the middle. At the top were added a neck, with a tall rim, and two handles, which were joined to the shoulder of the vessel. The belly is decorated with a low relief, depicting animals – alternately felines and birds – on a background of foliate elements. In the centre is a roundel containing a nine-petalled floral motif. Both the roundel and the overall design are surrounded by a border consisting of an interlocking chain pattern. The neck and the rim of the vessel have been restored; otherwise the piece is in fine condition.

Scholarship has been dismissive of the Umayyad and early Abbasid pottery, with one article suggesting that ‘there was little pottery of merit’ from the period. Most scholarly attention is drawn to the later Abbasid: in AD 800, the first traders from Tang Dynasty China made their way to the Abbasid heartland, and brought with them the decorative techniques of the Chinese potters. After then, Islamic pottery is associated with the same ingenious use of glazes, and the same experimentation with form and function, which characterises Chinese porcelain. However, there is much that is noteworthy about these early Umayyad and Abbasid attempts. While it may be unglazed, and the handiwork a little rough and ready, the elegance of the form, and the intricacy of the decoration should not be underestimated.

The Umayyads and the subsequent Abbasids laid the foundation for Islamic art. At first, the main influences were the Late Antique naturalistic tradition, and the more formal modes of Byzantine and Sassanid art. But gradually, the Islamic world began to formulate its own artistic forms, focussed especially on animal, vegetal and figural motifs. This conflation of the old and new can be seen in this large, unglazed, pilgrim flask. The form is very old indeed: pilgrim flasks are known from the early part of the Bronze Age in the Levant, and continued to be produced throughout the Roman and Byzantine Eras. Their name derives from this later period, when the form was used by Christian (and later Muslim) pilgrims to collect and store water which had been poured over sacred sites and objects. It consists of a large spherical body, moulded in two halves and joined with a hand-pressed seam in the middle. At the top were added a neck, with a tall rim, and two handles, which were joined to the shoulder of the vessel. The belly is decorated with a low relief, depicting animals – alternately felines and birds – on a background of foliate elements. In the centre is a roundel containing a nine-petalled floral motif. Both the roundel and the overall design are surrounded by a border consisting of an interlocking chain pattern. The neck and the rim of the vessel have been restored; otherwise the piece is in fine condition.

Scholarship has been dismissive of the Umayyad and early Abbasid pottery, with one article suggesting that ‘there was little pottery of merit’ from the period. Most scholarly attention is drawn to the later Abbasid: in AD 800, the first traders from Tang Dynasty China made their way to the Abbasid heartland, and brought with them the decorative techniques of the Chinese potters. After then, Islamic pottery is associated with the same ingenious use of glazes, and the same experimentation with form and function, which characterises Chinese porcelain. However, there is much that is noteworthy about these early Umayyad and Abbasid attempts. While it may be unglazed, and the handiwork a little rough and ready, the elegance of the form, and the intricacy of the decoration should not be underestimated.