Abbasid 'Happiness' Calligraphic Bowl, 9th Century CE

Ceramic, Pigment

6.3 x 21 cm

2 1/2 x 8 1/4 in

2 1/2 x 8 1/4 in

CC.272

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

The first attempt at a blue glaze in pottery occurred during the Third Millennium BC. Mesopotamian potters developed the earliest blue pigments to imitate much-prized, and exceptionally rare, lapis lazuli....

The first attempt at a blue glaze in pottery occurred during the Third Millennium BC. Mesopotamian potters developed the earliest blue pigments to imitate much-prized, and exceptionally rare, lapis lazuli. This technique was, however, lost. Instead, the modern tradition of blue glazes originated in China, during the Tang Dynasty. First produced in Henan Province in the Seventh Century AD, Chinese ‘white and blue’ wares (qīng-huā, literally ‘blue patterns’) were immediately and enduringly popular. Production ramped up during the Song Dynasty (AD 960 – AD 1279), and soon Chinese blue and white was being exported around the early-Mediaeval world. Geography meant that the main intermediaries in this trade were the Abbasid Caliphs, whose empire stretched from India to Tripoli, and from Yemen to Turkey. Controlling the western end of the famous Silk Road, the Abbasids acted as gatekeepers between East and West. Their merchants were the first to receive Chinese white and blue wares; Islamic potters somehow gained access to the secret of its production, either by close and careful examination of the wares themselves (and, presumably, much trial and error), or – more likely – through exchanges with Chinese potters. Given that cobalt oxide, the main ingredient in Chinese blue, was mined in central Iran, Oman and the Hejaz, we might postulate a trade in which the raw ingredient was exchanged for the secret of its manufacture and use. Additionally, earlier conflict between the Chinese and Abbasids at the Battle of Atlakh resulted in the capture of a number of Chinese potters and papermakers, who may have taught their secrets to their Muslim gaolers. But while imitation of Chinese wares became a major industry, the Abbasids still esteemed the real deal. One Arabic author, al-Sirafi, lamented that ‘the people of China are the most skilled in all Allah’s creation; they are not surpassed in designing and fabricating.’

In the Islamic world, the heavy reliance on figurative decoration demonstrated by the Chinese was rejected in favour of abstract and calligraphic designs. It is thought that the Abbasid Court was the direct sponsor of the Islamic pottery industry: one source, Ibn Naji (AD 1016), records that, after an earthquake destroyed the mihrab of Qairawan in AD 862, a ‘man from Baghdad’ was sent by the Abbasid government to replace the lusterware tiles. However, satellite pottery industries were soon set up, with a particularly active pottery in Basra, southern Iraq. Petrographic analysis of the clay of Abbasid blue and white wares has revealed that the clay, at least, came from the river to the south of Basra. Indeed, since Basra was a major port, it is possible that this is where Chinese wares first entered the Caliphate, and where the Islamic world first learned of Chinese blue and white pottery. Direct influence of Chinese wares is evident not only in the glaze, but also in the shape; both Abbasid and Chinese pottery was thrown in the same way, a process known as ‘jiggering’, whereby the vessel was thrown, then laid over a mould (a thrown pot with the approximate shape would fit the mould better than a flat pancake of clay). The mould was then spun on a wheel, allowing the potter to trim the excess clay, resulting in thin and smooth walls. The foot is then cut at a thirty degree angle, a foot ring is incised, and the vessel removed from the mould with either a wet slip or ash separating agent. The opacity of the white glaze was achieved through the addition of tin to the lead glaze; the higher the proportion of tin, the greater the opacity, whereas the higher the proportion of lead, the higher the lustre. Abbasid wares demonstrate considerable variability in their lead-tin ratio, as potters experimented to achieve the correct balance to imitate Chinese wares.

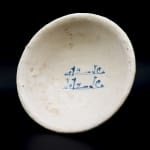

The blue decoration of these vessels is generally minimalistic, recognising that the harmonious beauty of the form itself did not require much embellishment. Characteristically, Abbasid wares bear a simple border of geometric shapes, and a calligraphic inscription. Often, the border was dispensed with, and the calligraphy was the sole decorative element. In the first phase of development, these calligraphic labels usually consisted of the potter’s signature. Given that many Chinese vessels were signed, this is seen as a close parallel to Chinese practice. Later vessels are known as ‘anonymous’ wares, since the potters dispensed with signatures in favour of religious, auspicious or valedictory words or phrases. This important Abbasid bowl comes in this latter phase. The white glaze is highly opaque, and moderately lustrous, indicating a high tin content in the glaze. The resulting milky-white surface accentuates the smooth and flowing shape. Rising from a short ring foot, the bowl is broad and low, with a gentle curve up to the highly everted rim. The opacity of the glaze makes it a perfect canvas for the calligraphic inscription. Written in an elaborate Kufic script with curvaceous flourishes and embellishments, known as floriated Kufic, the repeated inscription neatly contained in the tondo of the vessel reads simply ‘happiness’ or ‘good fortune’ (ghibta). The presence of this auspicious word on the bowl, repeated twice for emphasis, reflects an Arabic tradition of using inscriptions on the owners and users of tableware. Much as at a modern European dinner party, one might toast the health of the guests, at an Islamic feast, the very vessels from which one drank and ate expressed wishes for prosperity and fulfilment. A small errant spot of cobalt blue under the glaze above the inscription demonstrates something of the technique used, with powdered cobalt oxide applied under the final layer of white glaze.

References: similar bowls with the artist’s signature in floriated Kufic can be found in Oxford (Ashmolean Museum EA1978.2138), Copenhagen (Davids Samling Museum 21/1965), Turin (Museo d’Arte Orientale ISv/2), New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 63.16.2; Brooklyn Museum 88.227.14), Washington DC (Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Asian Art S1997.108, S1997.109). Floriated Kufic bowls with valedictory or auspicious inscriptions can be found in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 63.159.4 [ghibta]; Brooklyn Museum 74.195).

In the Islamic world, the heavy reliance on figurative decoration demonstrated by the Chinese was rejected in favour of abstract and calligraphic designs. It is thought that the Abbasid Court was the direct sponsor of the Islamic pottery industry: one source, Ibn Naji (AD 1016), records that, after an earthquake destroyed the mihrab of Qairawan in AD 862, a ‘man from Baghdad’ was sent by the Abbasid government to replace the lusterware tiles. However, satellite pottery industries were soon set up, with a particularly active pottery in Basra, southern Iraq. Petrographic analysis of the clay of Abbasid blue and white wares has revealed that the clay, at least, came from the river to the south of Basra. Indeed, since Basra was a major port, it is possible that this is where Chinese wares first entered the Caliphate, and where the Islamic world first learned of Chinese blue and white pottery. Direct influence of Chinese wares is evident not only in the glaze, but also in the shape; both Abbasid and Chinese pottery was thrown in the same way, a process known as ‘jiggering’, whereby the vessel was thrown, then laid over a mould (a thrown pot with the approximate shape would fit the mould better than a flat pancake of clay). The mould was then spun on a wheel, allowing the potter to trim the excess clay, resulting in thin and smooth walls. The foot is then cut at a thirty degree angle, a foot ring is incised, and the vessel removed from the mould with either a wet slip or ash separating agent. The opacity of the white glaze was achieved through the addition of tin to the lead glaze; the higher the proportion of tin, the greater the opacity, whereas the higher the proportion of lead, the higher the lustre. Abbasid wares demonstrate considerable variability in their lead-tin ratio, as potters experimented to achieve the correct balance to imitate Chinese wares.

The blue decoration of these vessels is generally minimalistic, recognising that the harmonious beauty of the form itself did not require much embellishment. Characteristically, Abbasid wares bear a simple border of geometric shapes, and a calligraphic inscription. Often, the border was dispensed with, and the calligraphy was the sole decorative element. In the first phase of development, these calligraphic labels usually consisted of the potter’s signature. Given that many Chinese vessels were signed, this is seen as a close parallel to Chinese practice. Later vessels are known as ‘anonymous’ wares, since the potters dispensed with signatures in favour of religious, auspicious or valedictory words or phrases. This important Abbasid bowl comes in this latter phase. The white glaze is highly opaque, and moderately lustrous, indicating a high tin content in the glaze. The resulting milky-white surface accentuates the smooth and flowing shape. Rising from a short ring foot, the bowl is broad and low, with a gentle curve up to the highly everted rim. The opacity of the glaze makes it a perfect canvas for the calligraphic inscription. Written in an elaborate Kufic script with curvaceous flourishes and embellishments, known as floriated Kufic, the repeated inscription neatly contained in the tondo of the vessel reads simply ‘happiness’ or ‘good fortune’ (ghibta). The presence of this auspicious word on the bowl, repeated twice for emphasis, reflects an Arabic tradition of using inscriptions on the owners and users of tableware. Much as at a modern European dinner party, one might toast the health of the guests, at an Islamic feast, the very vessels from which one drank and ate expressed wishes for prosperity and fulfilment. A small errant spot of cobalt blue under the glaze above the inscription demonstrates something of the technique used, with powdered cobalt oxide applied under the final layer of white glaze.

References: similar bowls with the artist’s signature in floriated Kufic can be found in Oxford (Ashmolean Museum EA1978.2138), Copenhagen (Davids Samling Museum 21/1965), Turin (Museo d’Arte Orientale ISv/2), New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 63.16.2; Brooklyn Museum 88.227.14), Washington DC (Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Asian Art S1997.108, S1997.109). Floriated Kufic bowls with valedictory or auspicious inscriptions can be found in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 63.159.4 [ghibta]; Brooklyn Museum 74.195).