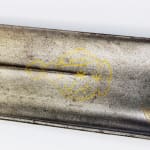

Damascened Afghan 'Khyber Knife' (Pesh-Kabz), Nineteenth Century AD

Steel, Gold, Soapstone

57.1 x 5.1 x 3.2 cm

22 1/2 x 2 x 1 1/4 in

22 1/2 x 2 x 1 1/4 in

CC.279

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

The Muslim world could not imagine a universe without chainmail armour. According to the Qur’an, mail was introduced to King David (c. 1000 BC) by Allah himself: ‘it was We...

The Muslim world could not imagine a universe without chainmail armour. According to the Qur’an, mail was introduced to King David (c. 1000 BC) by Allah himself: ‘it was We [Allah] who taught the making of coats of mail for his [David’s] benefit’ (281:80). In fact, mail armour was introduced much later than David, by the Romans, and was adopted by the Sassanid Persians in the Third Century AD. Islamic mail was flexible, less heavy than plate armour, and was both practically and spiritually effective: blacksmiths worked Qur’anic phrases onto the tiny metal links, to provide additional divine protection. Chain mail prompted something of an arms race, however. Highly effective against slashing weapons, such as sabres, chainmail was preferred by heavy cavalry (cataphracts) and light infantry. Instead, weapon-smiths developed piercing and stabbing weapons, designed to force their way between the links of the mail. Islamic soldiers were still wearing mail in the Seventeenth Century AD, long after armour had been rendered ineffective in Europe by ranged gunpowder weapons, and the Safavid Persian swordsmiths created a new weapon to combat it: the pesh-kabz.

The pesh-kabz consists of a full-tang tempered steel blade, with handle pieces affixed. The blade itself is a long and tapering recurve blade, which reaches a needle-like point. Instead of a cross-guard or hilt, the blade itself flares into a T-shaped cross section which protects the hand of the user. When it came into contact with mail, this reinforced tip split the chain-links apart, and the slight recurve of the blade allowed it to be thrust through the armour effectively without getting caught on the links on the way in or, importantly, out. One of the most respected experts on ancient weaponry, the late G. C. Stone, wrote that ‘as a piece of engineering design, the pesh-kabz could hardly be improved upon for the purpose’ (Stone, G. C. (1934) A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armour in All Countries and in All Times. Portland, ME: pp. 493-4). The design rapidly spread from Persia to the surrounding areas, and became especially popular in Afghanistan (where they were known as choora) and Mughal India. The British conquerors of India dubbed the weapons ‘Khyber Knives’, after the infamous Khyber Pass. A valley in the White Mountains which separate modern Pakistan from Afghanistan, the Khyber Pass was the gateway between Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent. As such, it has been fought over by great empires from the Sixth Century BC, and was the route by which the Achaemenids Cyrus and Darius I, the Macedonian Alexander the Great, the Mongol Genghis Khan, the Turkic Tamerlane, and the Moghul Babur entered India. In the Nineteenth Century, the British colonial governors of India became concerned about Russian influence over Afghanistan, and used their own military might to impose their will upon the Afghans. Three Anglo-Afghan Wars resulted, in which the British made significant military gains. None of the wars, however, resulted in sustainable British occupation of Afghanistan: the fierce local tribal structures provided stiff resistance, and, partly through choice and partly through necessity, the British withdrew on each occasion. The Khyber Pass became a valley of death, in which British troops were vulnerable to ambush from the local Pashtuns, and which entered the British imperial mythos. Armed with ‘Khyber Knives’, the local Pashtun warlords earned the respect of the British, and the pesh-kabz became a symbol both of Afghan resistance and independence from European colonialism.

This exceptional damascened pesh-kabz must have been owned by a tribal leader. The handle is made from soapstone, rather than the traditional walrus ivory (Persian dandan-mahi), in a nod to the variety of beautiful pale veined hardstones endemic to Afghanistan’s mountains. While not considered a precious stone by Europeans, soapstone was thought by the locals to be an equivalent to, or even type of, jade, and was valued as such. The blade, made from tempered steel, is inlaid with gold, a process known in Europe as damascening, from its resemblance to the rich patterns of damask silk. The damascened inlays – created from laying gold wire into incisions in the surface of hot steel – contain inscriptions in Persian, reflecting the ultimate origins of the pesh-kabz in the Safavid Empire. This may imply that this dagger originated in Iran or even Pakistan, where Persian and Urdu were spoken commonly. The texts are unclear, expressed in a loose and flowing form of Persian calligraphy (nasta’liq), and contain decorative additions which obfuscate their meaning, but appear to be Persian aphorisms, and perhaps the maker or owner’s name (perhaps reading Hayd bin Tab) The texts are framed by cartouches, one which follows the shape of the blade near the hilt, and is made up of dense arabesques, and the other in an organic, floriate form, known from other Persian weapons (e.g. Royal Collection Trust RCIN 11283). Each side of the blade has a fuller, a groove down the centre, which reduces the weight of the blade while protecting its strength and structural integrity.

References: ‘Khyber Knives’ of similar design appear in numerous collections, including in London (British Museum As1982,11.6, Imperial War Museum WEA 2266, Horniman Museum nn.18533.1, National Army Museum 1951-01-23-1), and a damascened knife in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 36.25.814).

The pesh-kabz consists of a full-tang tempered steel blade, with handle pieces affixed. The blade itself is a long and tapering recurve blade, which reaches a needle-like point. Instead of a cross-guard or hilt, the blade itself flares into a T-shaped cross section which protects the hand of the user. When it came into contact with mail, this reinforced tip split the chain-links apart, and the slight recurve of the blade allowed it to be thrust through the armour effectively without getting caught on the links on the way in or, importantly, out. One of the most respected experts on ancient weaponry, the late G. C. Stone, wrote that ‘as a piece of engineering design, the pesh-kabz could hardly be improved upon for the purpose’ (Stone, G. C. (1934) A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armour in All Countries and in All Times. Portland, ME: pp. 493-4). The design rapidly spread from Persia to the surrounding areas, and became especially popular in Afghanistan (where they were known as choora) and Mughal India. The British conquerors of India dubbed the weapons ‘Khyber Knives’, after the infamous Khyber Pass. A valley in the White Mountains which separate modern Pakistan from Afghanistan, the Khyber Pass was the gateway between Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent. As such, it has been fought over by great empires from the Sixth Century BC, and was the route by which the Achaemenids Cyrus and Darius I, the Macedonian Alexander the Great, the Mongol Genghis Khan, the Turkic Tamerlane, and the Moghul Babur entered India. In the Nineteenth Century, the British colonial governors of India became concerned about Russian influence over Afghanistan, and used their own military might to impose their will upon the Afghans. Three Anglo-Afghan Wars resulted, in which the British made significant military gains. None of the wars, however, resulted in sustainable British occupation of Afghanistan: the fierce local tribal structures provided stiff resistance, and, partly through choice and partly through necessity, the British withdrew on each occasion. The Khyber Pass became a valley of death, in which British troops were vulnerable to ambush from the local Pashtuns, and which entered the British imperial mythos. Armed with ‘Khyber Knives’, the local Pashtun warlords earned the respect of the British, and the pesh-kabz became a symbol both of Afghan resistance and independence from European colonialism.

This exceptional damascened pesh-kabz must have been owned by a tribal leader. The handle is made from soapstone, rather than the traditional walrus ivory (Persian dandan-mahi), in a nod to the variety of beautiful pale veined hardstones endemic to Afghanistan’s mountains. While not considered a precious stone by Europeans, soapstone was thought by the locals to be an equivalent to, or even type of, jade, and was valued as such. The blade, made from tempered steel, is inlaid with gold, a process known in Europe as damascening, from its resemblance to the rich patterns of damask silk. The damascened inlays – created from laying gold wire into incisions in the surface of hot steel – contain inscriptions in Persian, reflecting the ultimate origins of the pesh-kabz in the Safavid Empire. This may imply that this dagger originated in Iran or even Pakistan, where Persian and Urdu were spoken commonly. The texts are unclear, expressed in a loose and flowing form of Persian calligraphy (nasta’liq), and contain decorative additions which obfuscate their meaning, but appear to be Persian aphorisms, and perhaps the maker or owner’s name (perhaps reading Hayd bin Tab) The texts are framed by cartouches, one which follows the shape of the blade near the hilt, and is made up of dense arabesques, and the other in an organic, floriate form, known from other Persian weapons (e.g. Royal Collection Trust RCIN 11283). Each side of the blade has a fuller, a groove down the centre, which reduces the weight of the blade while protecting its strength and structural integrity.

References: ‘Khyber Knives’ of similar design appear in numerous collections, including in London (British Museum As1982,11.6, Imperial War Museum WEA 2266, Horniman Museum nn.18533.1, National Army Museum 1951-01-23-1), and a damascened knife in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 36.25.814).