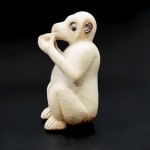

Bactrian Figure of a Monkey Drinking, Third Millennium BC

Calcite, Chlorite, Diorite, Jasper

12.2 x 8.2 x 6.6 cm

4 3/4 x 3 1/4 x 2 5/8 in

4 3/4 x 3 1/4 x 2 5/8 in

CC.286

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

In the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, the mysterious civilisation discovered by Soviet scientists in the middle of the Twentieth Century AD, the animal world and the human world existed in close...

In the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, the mysterious civilisation discovered by Soviet scientists in the middle of the Twentieth Century AD, the animal world and the human world existed in close contact. Human beings relied on animals for many aspects of their daily lives. Cattle were used to drive ploughs, pull carts, trample seeds, and fertilise the fields. Dogs would doubtless have been used for hunting, herding, war and companionship. Horses and camels were vital beasts of burden, and also important for transporting individuals and goods around the disparate Bactria=Margiana Region. These animals were also a reference to the nomadic background of the BMAC. And frequent interactions with the animals of the wild shaped aspects of the Bactrian imagination. Lions, for example, both alone and in combat with one another, were a frequent motif in Bactrian art, probably representing the strength and vivacity of the ruler. But there is another recurring class of Bactrian animal figures which requires more detailed explanation: imaginative, charming, endearing representations of monkeys in various scenarios, some of which assimilate them to humans.

The spiritual and religious importance of animals in BMAC culture is only now beginning to emerge. At the site of Gonur Depe in southern Turkmenistan, recent excavations have revealed more than seventy animal burials, over half of which have their own grave goods. While the animals at Gonur Depe are mostly dogs, cattle, horses and camels, another recently-discovered burial – from near the Afghanistan-Iran border, and dating from 2800 BC – was of a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), complete with pottery and other grave goods. The ritual burial of animals throughout the territory of the BMAC suggest something far beyond the simply interment of family pets or work animals. Instead, it is possible that these animals were special sacrifices to relevant gods – similar to the burial of mummified animals in Egypt from around the same time – or that they were being honoured in some other way. In other cultures, monkeys have multiplicitous symbolic meanings, including wisdom, youth, good fortune, trickery and guardianship. It is reasonable to assume that at least some of these meanings existed for the Bactrians

It is probable that this monkey represents the rhesus macaque. His muzzle is elongated, with a round chin; his eyes are round, intense and wide; his nose petite, and his body pear-shaped. He rests on his haunches, his feet in front of him, in a pose which will be familiar to anyone who has seen rhesus macaques sat around human settlements in Nepal and India. The arms are long and fingers extended, and this is another feature associated with Macaca mulatta. The monkey seems relaxed, even happy, and stares at the viewer with a kind of positivity and lightness in his expression. Beautifully carved, from white calcite, his eyes are inlaid with chlorite and diorite, with hints of other stones in his ears and nose. The attention paid to the dome of the eyeball, the green irises contrasting with the near-black pupils, demonstrates an incredible level of skill on the part of the artisan. The monkey raises some kind of bowl to his lips, as thought about to take a drink. His expression, pose, and action is incredibly human. Indeed, monkeys, when kept as pets, are very adept at mimicking human action, and so this may represent a domesticated monkey copying his masters. Alternatively, the monkey may represent an image of a primate from myth or allegory, who perhaps took on the affectations and attributes of the humans. His underside shows evidence that he was, at some point, resting on or attached to a bronze stand, plate or other object.

The spiritual and religious importance of animals in BMAC culture is only now beginning to emerge. At the site of Gonur Depe in southern Turkmenistan, recent excavations have revealed more than seventy animal burials, over half of which have their own grave goods. While the animals at Gonur Depe are mostly dogs, cattle, horses and camels, another recently-discovered burial – from near the Afghanistan-Iran border, and dating from 2800 BC – was of a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), complete with pottery and other grave goods. The ritual burial of animals throughout the territory of the BMAC suggest something far beyond the simply interment of family pets or work animals. Instead, it is possible that these animals were special sacrifices to relevant gods – similar to the burial of mummified animals in Egypt from around the same time – or that they were being honoured in some other way. In other cultures, monkeys have multiplicitous symbolic meanings, including wisdom, youth, good fortune, trickery and guardianship. It is reasonable to assume that at least some of these meanings existed for the Bactrians

It is probable that this monkey represents the rhesus macaque. His muzzle is elongated, with a round chin; his eyes are round, intense and wide; his nose petite, and his body pear-shaped. He rests on his haunches, his feet in front of him, in a pose which will be familiar to anyone who has seen rhesus macaques sat around human settlements in Nepal and India. The arms are long and fingers extended, and this is another feature associated with Macaca mulatta. The monkey seems relaxed, even happy, and stares at the viewer with a kind of positivity and lightness in his expression. Beautifully carved, from white calcite, his eyes are inlaid with chlorite and diorite, with hints of other stones in his ears and nose. The attention paid to the dome of the eyeball, the green irises contrasting with the near-black pupils, demonstrates an incredible level of skill on the part of the artisan. The monkey raises some kind of bowl to his lips, as thought about to take a drink. His expression, pose, and action is incredibly human. Indeed, monkeys, when kept as pets, are very adept at mimicking human action, and so this may represent a domesticated monkey copying his masters. Alternatively, the monkey may represent an image of a primate from myth or allegory, who perhaps took on the affectations and attributes of the humans. His underside shows evidence that he was, at some point, resting on or attached to a bronze stand, plate or other object.