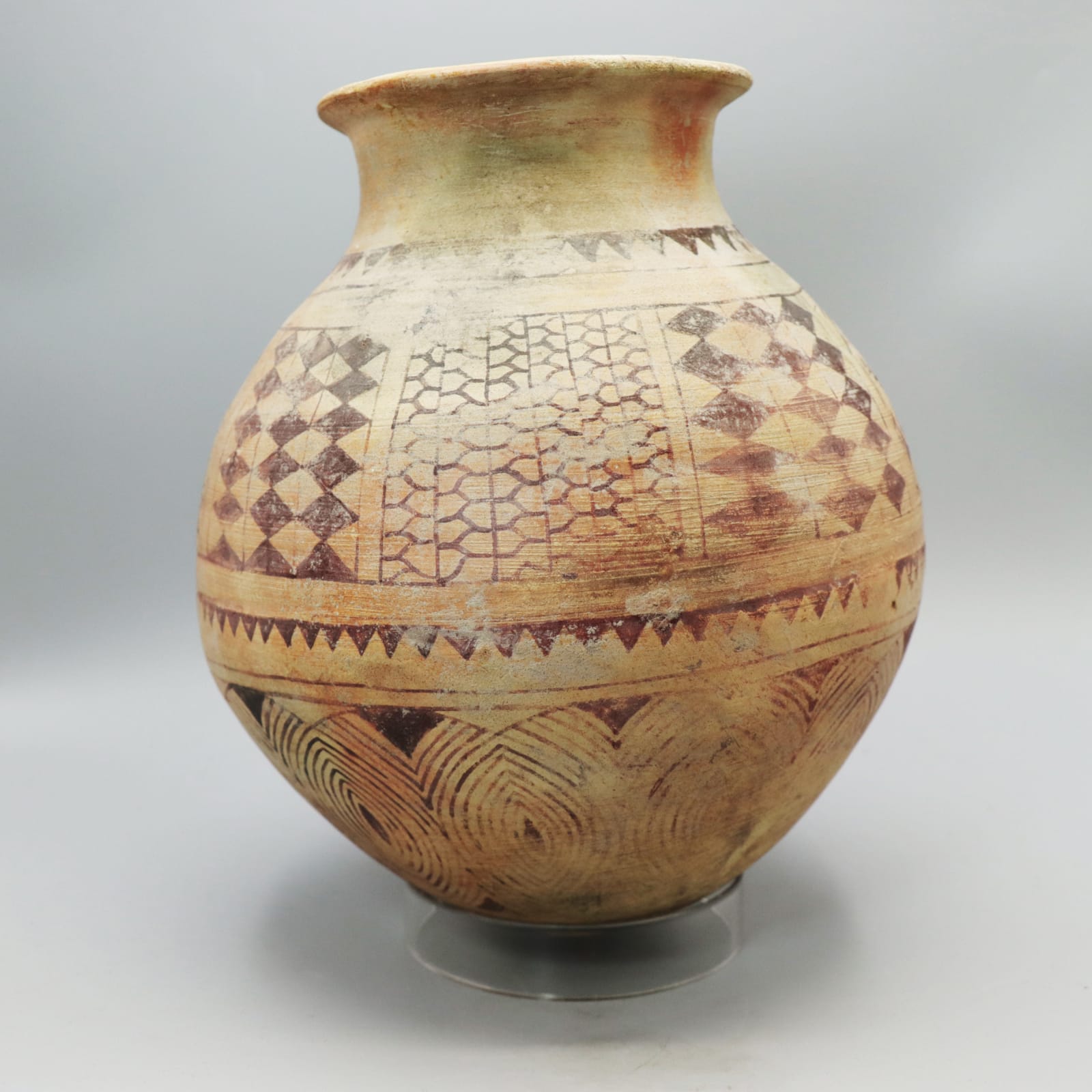

Elamite Decorated Vase, 1600 BC - 1300 BC

Terracotta, Pigment

24.1 x 21.6 cm

9 1/2 x 8 1/2 in

9 1/2 x 8 1/2 in

LK.122

In an arc which stretched from the River Indus in the East to the River Nile in the West, the first major civilisations appeared. Right in the centre of this...

In an arc which stretched from the River Indus in the East to the River Nile in the West, the first major civilisations appeared. Right in the centre of this arc, known to archaeologists as the Fertile Crescent, was Elam. Centred on what is now western Iran and south-eastern Iraq, the Elamite culture emerged during the Chalcolithic (a period where the first metal objects were created) around 3000 BC. The Elamites, contemporaneous with the Mesopotamian civilisations of Sumer and Ur, Elam participated in the early urbanisation of the Near East, founding the important city of Susa. It took an invasion by the Mongols in AD 1218, some 5,000 years later, for Susa to collapse. The Elamites were also among the first to develop writing, with this innovation occurring around the same time as in neighbouring Sumer. But despite their rich history and material culture, and despite the important role they played in the early history of humankind in the Afro-Eurasian region, little is known about the Elamites. What is known comes largely from mentions in the Sumerian, Mesopotamian, and later Biblical, sources.

But while the Elamites cannot speak for themselves in the historical record, the artefacts they left behind give us glimpses into the life and culture of Elam. This exceptional vase dates to the late Bronze Age, known as the Middle Elamite Period. This period was something of a renaissance: having begun to use the Akkadian language, under the influence of their neighbours, the Elamite language experienced a resurgence. The richness of the archaeological record in and around this period also indicates that the major Elamite centres, notably Susa, enjoyed a revitalisation of their fortunes. Susa became the capital of the whole region, and a major centre for the tributary relationship which the Elamites exacted from their neighbours. By the 1200s BC, Susa was benefiting from a number of military campaigns into neighbouring territories – especially Babylonia, which was also being ravaged by the Assyrians – which gave access to plentiful resources. The temples in Susa were kitted out in a luxurious fashion by powerful kings including Shutruk-Nakhkhunte and Kutir-Nakhkhunte II. In this beautiful vase, we see the benefits of these international contacts, and of the Elamites’ newfound wealth, reaching the hands of the middle classes.

Of an elegant shape, with an ovoid body, wide neck, and everted rim, the curved bottom of this vessel indicates that it was never meant to stand up on its own. Instead, it would have either sat in a stand, or more likely would have been twisted into the sand. It is decorated in black pigment, which still retains some of its richness despite the intervening years. The lower register depicts a motif of pointed arches, which seem to draw on leaves and other organic forms. The lower and upper registers are separated by a band of downward pointing triangles. The upper register consists of eight panels; four with a pattern of diamonds, two with a honeycomb motif, and two with a series of animals. The animals include deer, represented as two curved triangles, a circular head, a line for a muzzle, and antlers; teardrop-shaped birds with dotted patterns; ibex depicted like the deer but with curved horns; and a mysterious animal depicted as a right-angled triangle with a dotted coat, human-like feet, two short arms, a triangular head, and antlers. The focus on wild animals is something the Elamites seem to have imported from their trading-partners in the Indus Valley.

But while the Elamites cannot speak for themselves in the historical record, the artefacts they left behind give us glimpses into the life and culture of Elam. This exceptional vase dates to the late Bronze Age, known as the Middle Elamite Period. This period was something of a renaissance: having begun to use the Akkadian language, under the influence of their neighbours, the Elamite language experienced a resurgence. The richness of the archaeological record in and around this period also indicates that the major Elamite centres, notably Susa, enjoyed a revitalisation of their fortunes. Susa became the capital of the whole region, and a major centre for the tributary relationship which the Elamites exacted from their neighbours. By the 1200s BC, Susa was benefiting from a number of military campaigns into neighbouring territories – especially Babylonia, which was also being ravaged by the Assyrians – which gave access to plentiful resources. The temples in Susa were kitted out in a luxurious fashion by powerful kings including Shutruk-Nakhkhunte and Kutir-Nakhkhunte II. In this beautiful vase, we see the benefits of these international contacts, and of the Elamites’ newfound wealth, reaching the hands of the middle classes.

Of an elegant shape, with an ovoid body, wide neck, and everted rim, the curved bottom of this vessel indicates that it was never meant to stand up on its own. Instead, it would have either sat in a stand, or more likely would have been twisted into the sand. It is decorated in black pigment, which still retains some of its richness despite the intervening years. The lower register depicts a motif of pointed arches, which seem to draw on leaves and other organic forms. The lower and upper registers are separated by a band of downward pointing triangles. The upper register consists of eight panels; four with a pattern of diamonds, two with a honeycomb motif, and two with a series of animals. The animals include deer, represented as two curved triangles, a circular head, a line for a muzzle, and antlers; teardrop-shaped birds with dotted patterns; ibex depicted like the deer but with curved horns; and a mysterious animal depicted as a right-angled triangle with a dotted coat, human-like feet, two short arms, a triangular head, and antlers. The focus on wild animals is something the Elamites seem to have imported from their trading-partners in the Indus Valley.